CURATORS ESSAY

UPCYCLING IN LATIN AMERICA:

A LONG TRADITION

by adélia borges

Adélia Borges

São Paulo, Brazil

Pure Gold Curator for

Latin America

Adélia Borges is a freelance design curator, journalist and writer based in São Paulo. She is a former director of the design museum Museu da Casa Brasileira, and has curated forty-eight exhibitions in seven countries, among them Novos alquimistas (Belo Horizonte, 2000), Uma história do sentar (Curitiba, 2002), Kumurõ: Bancos indígenas da Amazônia (Paris, 2005), Design contemporâneo brasileiro (San Francisco, 2005), Ícones do design: França/Brasil (Rio de Janeiro, 2009), Bienal Brasileira de Design (Curitiba, 2010), In Praise of Diversity (Amsterdam, 2012) and Origens do Brasil (Milan, 2014).

She has authored or co-authored more than fifteen books, among them Design + Artesanato: o caminho brasileiro (2011), Designer não é personal trainer (2009), and Móvel brasileiro contemporâneo (2013).

As a journalist, she was the director of the magazine Design & Interiores (1987–1994), the design editor of Gazeta Mercantil, a daily business newspaper (1998–2002), and a freelancer writer for many Brazilian and international magazines (Indaba in South Africa, Interni in Italy, Axis in Japan, etc.). Her articles, books and chapters for books have been published in Portuguese, German, Korean, Spanish, French, English, Italian and Japanese.

She has been a member of the nominator team of the London Design Museum/Designs of the Year award since 2010 and the international advisory committee of London Design Biennale since 2016. She is a member of the advisory curatorial team at the Design Triennial of Cooper-Hewitt Design Museum, New York, 2016. She promotes popular culture and design in Latin America and strives to bring together industrial and craft design. She believes that the southern hemisphere, with its rich cultural heritage, must be proud of its roots and need not copy other cultures.

UPCYCLING IN LATIN AMERICA: A LONG TRADITION by ADÉLIA BORGES

Reusing cheap materials or garbage to create new objects and extending their life cycle has been part of Latin American material culture for a long time. Whereas in parts of the world like Europe this practice derives from environmental awareness, in these countries it derives from an inventiveness dictated by a need for survival.

Poverty historically created vast population clusters marginalized from consumer society. Lack of access to industrially manufactured goods prompted people to use their own hands to create and make objects aimed at satisfying their everyday needs.

In Brazil, up to the 1970s, the population was predominantly rural. Creating objects for family or community use was based on natural local elements as raw materials. Straw would become baskets to carry supplies, woven hammocks to sleep in or the rooves of homes; clay would be transformed into vessels to store water and into plates to eat from; tree branches and trunks combined with leather from animals would result in items of furniture. In the country dubbed as the one with the greatest biodiversity in the world, there is no shortage of raw materials to supply the different requirements of resistance, lightness, durability, and adaptability to the local climate in various typologies of objects.

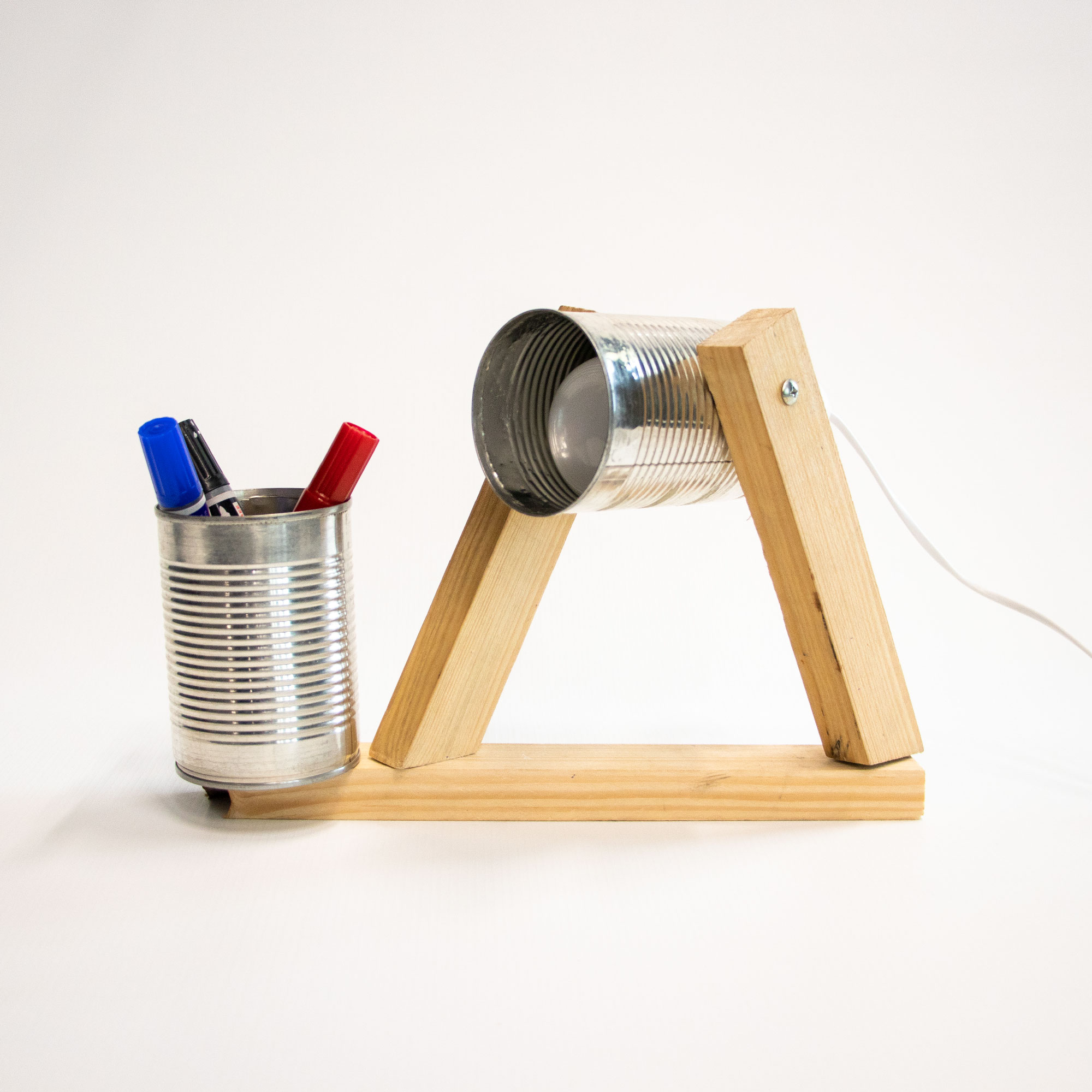

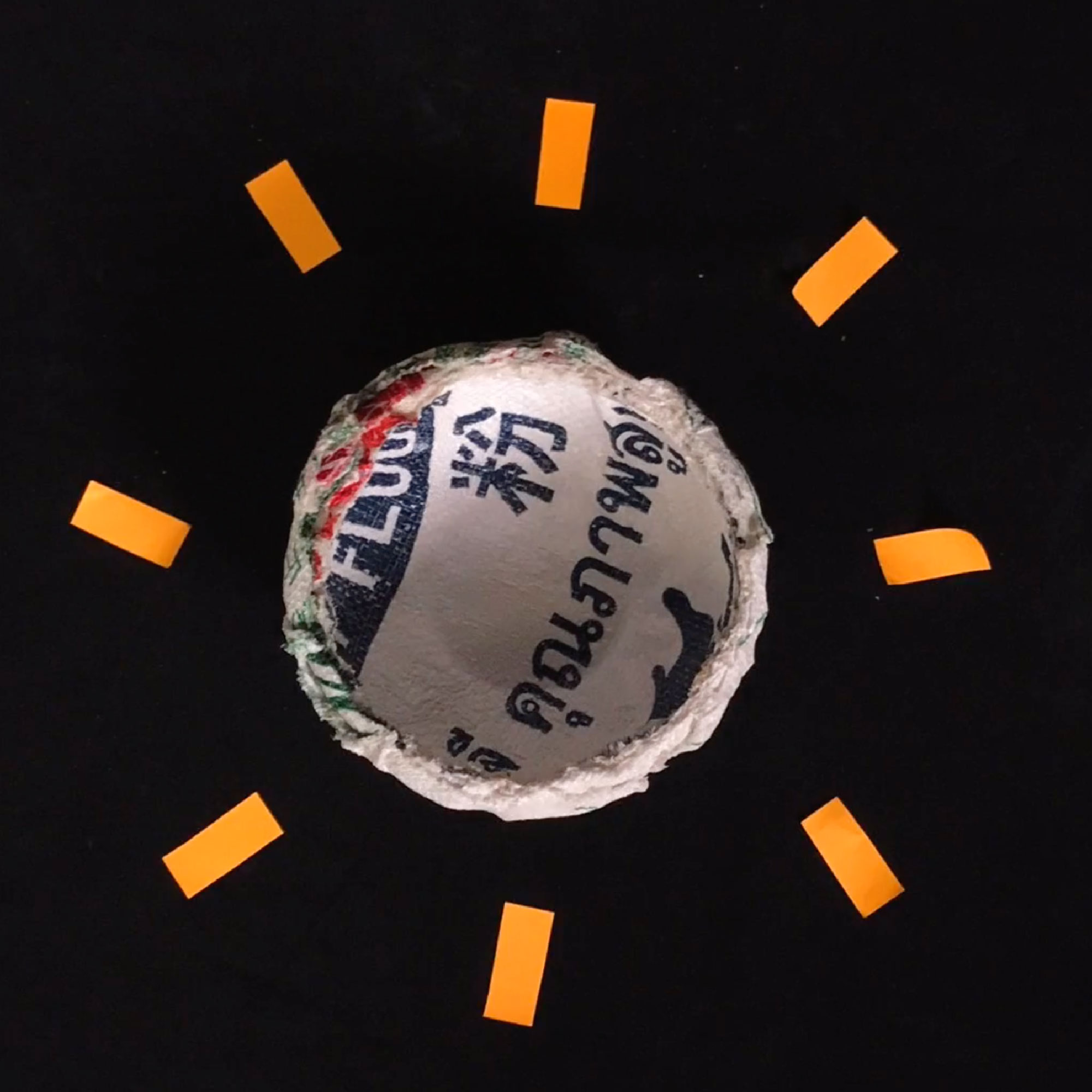

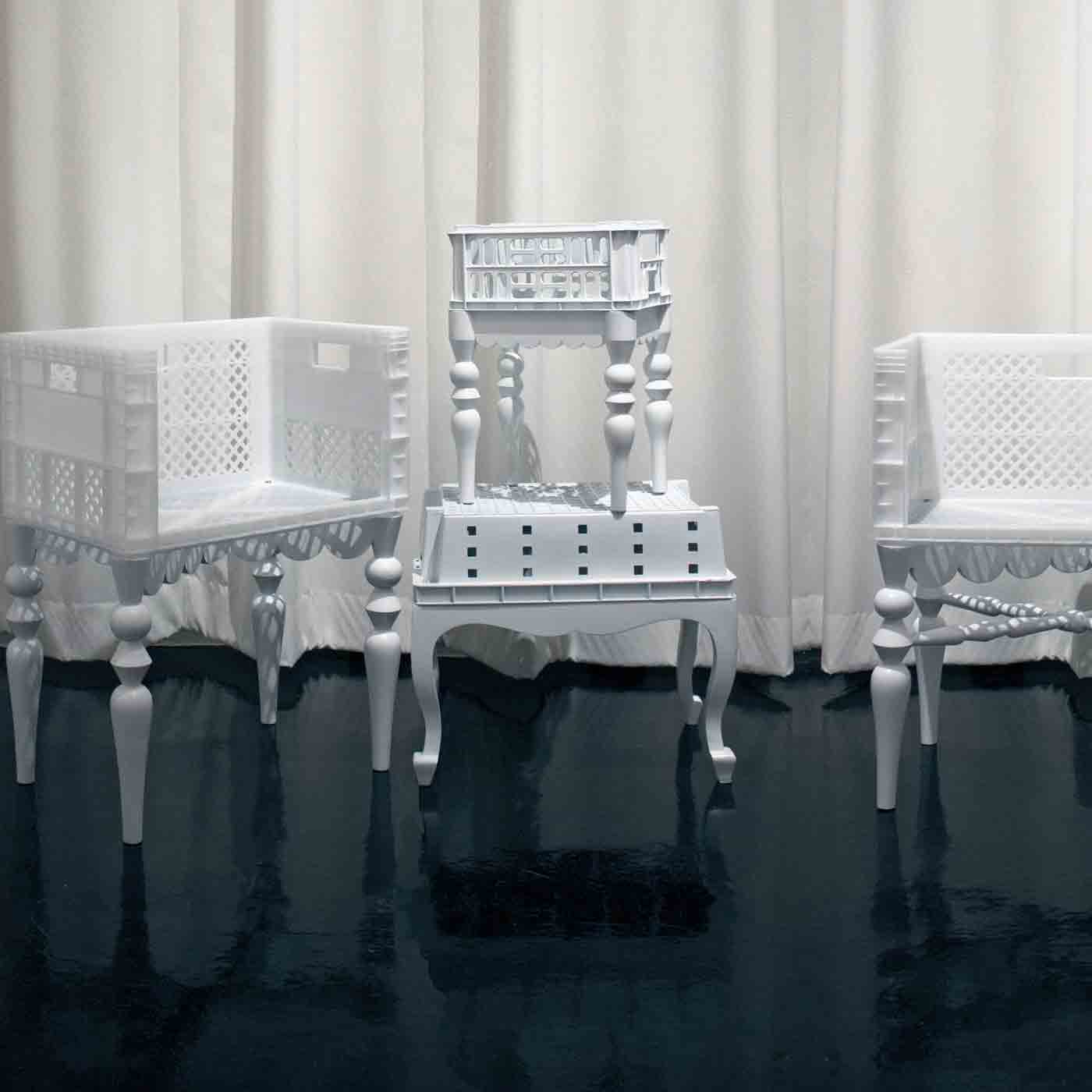

With growing urbanization, materials derived from industrial society’s leftovers were added to naturally available materials. The garbage of the wealthiest became raw materials for the population brackets on the base of the pyramid. Thus, reusing leftovers, as “infected” as they might seem, became an everyday practice. Another frequent attitude was to dislocate objects from the functions they were primarily made to serve to adapt them to new functions.

The Italian architect Lina Bo Bardi (1914–1992), who came to Brazil in the 1940s and stayed to end of her days, admiringly documented these practices, which she came to know in the late 1950s when she started to work in Bahia state, in the northeastern region of the country, poorer than industrialized São Paulo, where she had been living up to then. Lina fell in love with quilts made from small fabric scraps and with utensils created through reusing various aluminium packaging. Paradigmatic objects she collected during her wanderings were kerosene lamps used to light homes with no electric power supply, made of garbage – ironically, some of them use discarded burnout bulbs as the container for the combustible fluid.

Another intellectual who was deeply interested in such practices was designer Aloísio Magalhães (1927–1982). In the 1970s, he created the Centro Nacional de Referência Cultural (National Centre of Cultural Reference), which documented local efforts. Aloísio was motivated by a question by the then Brazilian minister of Industry and Commerce Severo Gomes, who asked why Brazilian products did not have their own character. According to the designer, this was due to unfamiliarity to Brazilian material culture.

As head of the Centre, Aloísio conducted research on textiles, ceramics production, beverage labels, budget brands, indigenous crafts, and the re cycling of industrial leftovers, among other themes, all carried out in order to explore the character of Brazilian products and designs.

The Centre was a public institution trying to question the function-oriented quality dominating institutionalized Brazilian design at the time, which was due to the great influence of the German Ulm School of Design model on the first design school established in Brazil – Escola Superior de Desenho Industrial (ESDI; Higher Education School of Industrial Design), founded in Rio de Janeiro in 1963. ESDI’s pro-gramme followed that of the Ulm School, from where some of the professors came. Adoption of this international style had become a prevailing power not only at ESDI, but also at schools opened later and in the everyday activities of designers.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, echoes of concerns regarding “recycling in design” started to get to Brazil, coming particularly from Europe, along with environmental initiatives against exaggerated consumerism and a sense of anxiety at having more and more stuff based on a Western way of life. Expressions such as “Kleenex culture” came to critically represent this mentality, as did “use and discard”. Those movements started to question the very use of the expression “to discard”. After all, what is really discarded? If it is no longer at home, it is still part of the town, of the country – and ultimately – of the world. Cargo ships transport compacted waste from highly industrial-ized countries to far-away places in the southern hemisphere, trying to “discard” their filth. However, this will continue to be “within” the planet. We needed to start to look at waste as the only resource grow-ing in the planet, as the American thinker Buckminster Fuller foretold.

Those international echoes came to Latin America, ironically at a time when many countries in the region – Brazil included – were going through great economic booms, weakening the population‘s recycling efforts. Thus, through international environmental movements fuelled by a growing environmental crisis, reuse initiatives gained new meaning – now as positioning statements, and almost like an ideological manifesto for the planet’s future. The ideas of some branches of design in the northern hemisphere also influenced Latin America, expressed, for instance, in the Con-scious, Simple – Consciously Simple exhibition curated by Volker Albus and completed in 1998 by ifa, which later, in May 1999, came to Museu da Casa Brasileira in São Paulo. Albus showed an alternative culture of products conceived, produced and handled in a consciously simple way, which represented a shock to Brazilian ears used to the Ulm School’s industrial pragmatism.[1]

In November of the same year, at the Novos alquimistas (New Alchemists) exhibition at Itaú Cultural, I gathered objects resulting from cheap materials or garbage upcycling. In the same exhibition space, vernacular creations by people with no instruction from around the country stood side by side with the work of educated designers who sought inspiration both in Brazilian traditional culture and in new ideas emerging from discussions in the northern hemisphere. Many designers taking part in the show referred to their grandparents as “recycling masters”, people capable of reusing everything, of trans-forming waste into gold.

As I noted in the catalogue, “recycling, reusing, recontextualizing became part of our everyday lives, and not only in the realm of objects. Graphic design changed with image scanning and distorting made possible through a computer. In fashion, from the grunges as inspiration, also to haute couture, it came to the streets. Samplers are very present in the universe of pop, and other music movements take advantage of reusing elements of the traditional local culture and of other worlds. The dictatorship of ‘good taste’ no longer exists, in any domain. Recirculation of information, forms, and sound marks our everyday lives. In the field of objects, it does not matter what are the nuances of each different country, there is a common questioning of the type of progress adopted by industrial society.”[2]

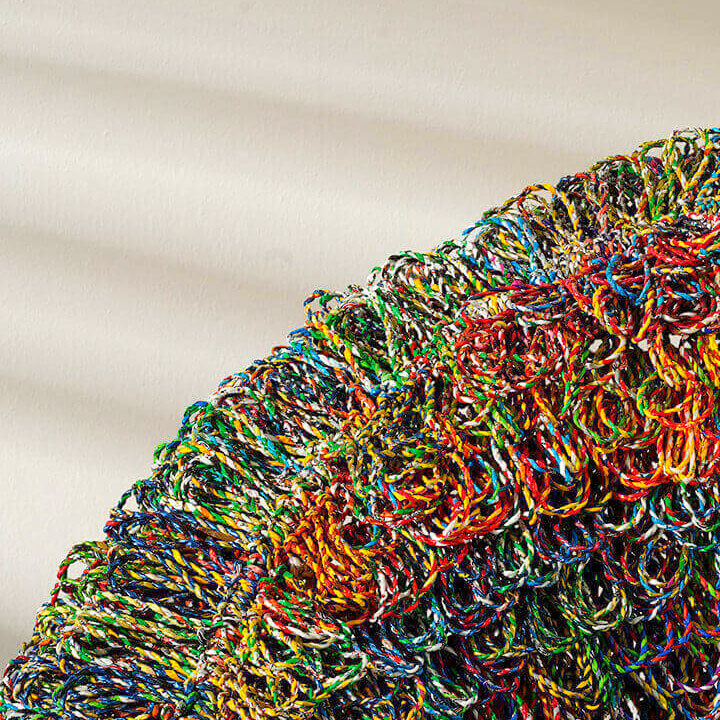

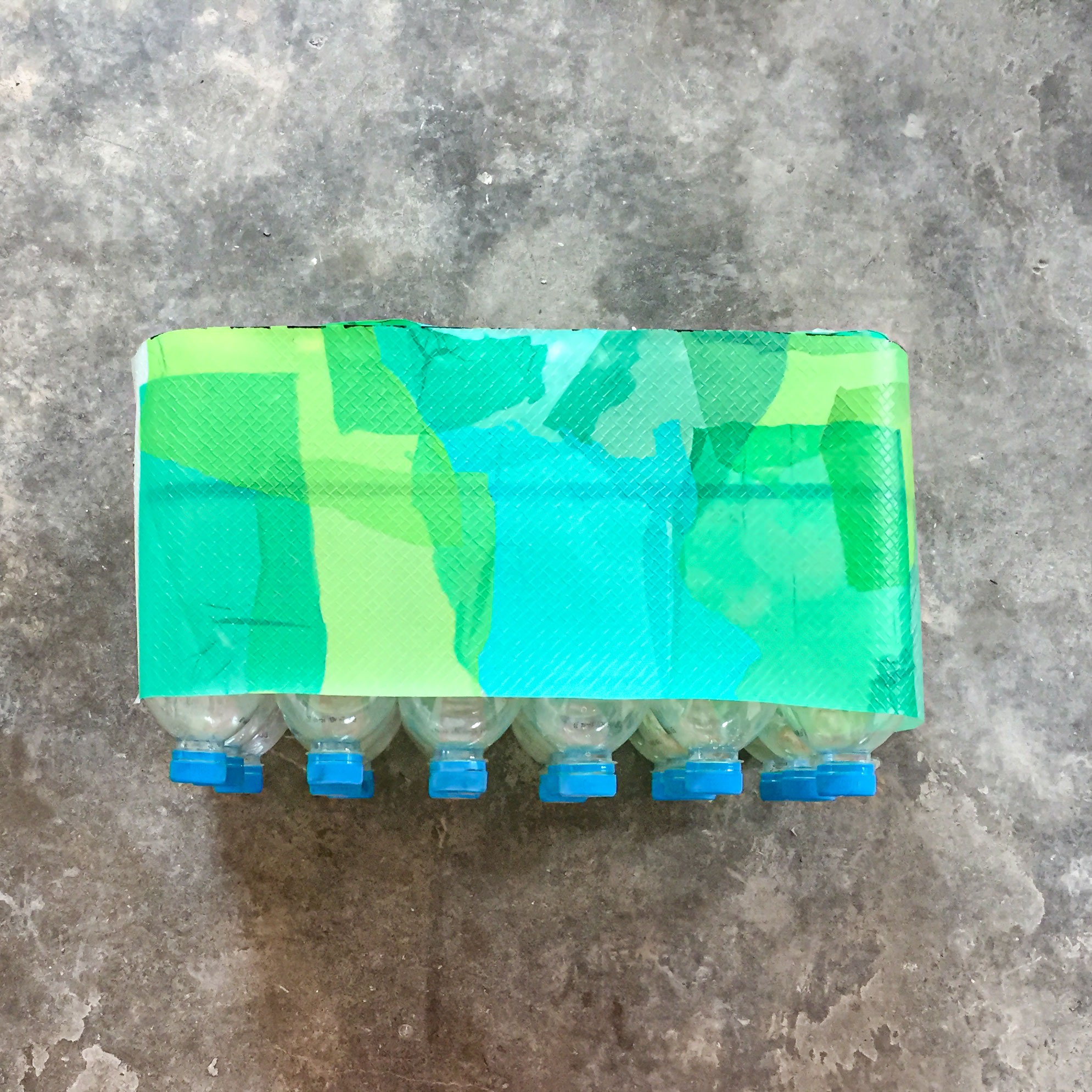

Latin American designers now selected for Pure Gold reveal their double influence of internal vernacular design and of social movements touching international design. Brunno Jahara and Domingos Tótora from Brazil and Colectivo Ático de Diseño from Argentina are relatively new protagonists in the scene, and even though they share similar views regarding design today, each of them chooses different procedures.

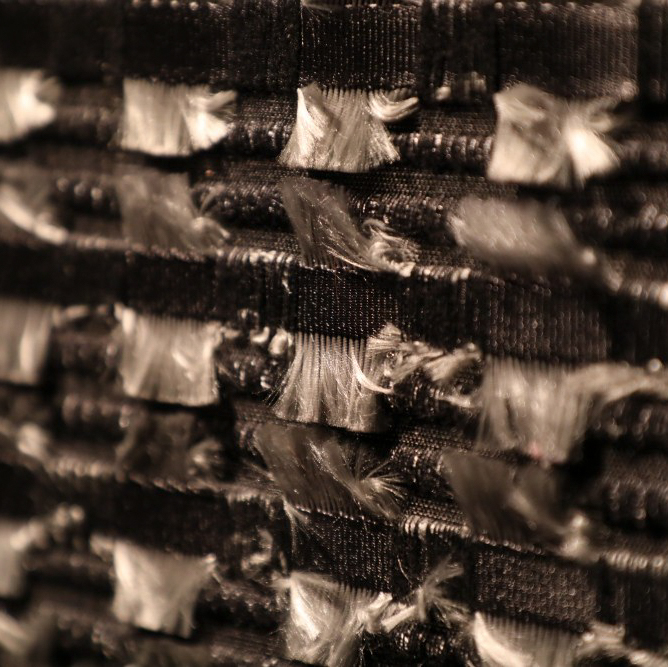

Domingos Tótora starts by designing his raw materials themselves, developed from discarded cardboard packaging. This is not simple reuse, as a whole new process is involved in the transformation of the material. Cardboard is mixed with water and glue, and then pressed and moulded, acquiring resistance. Only later will it gain the forms imagined by the designer.

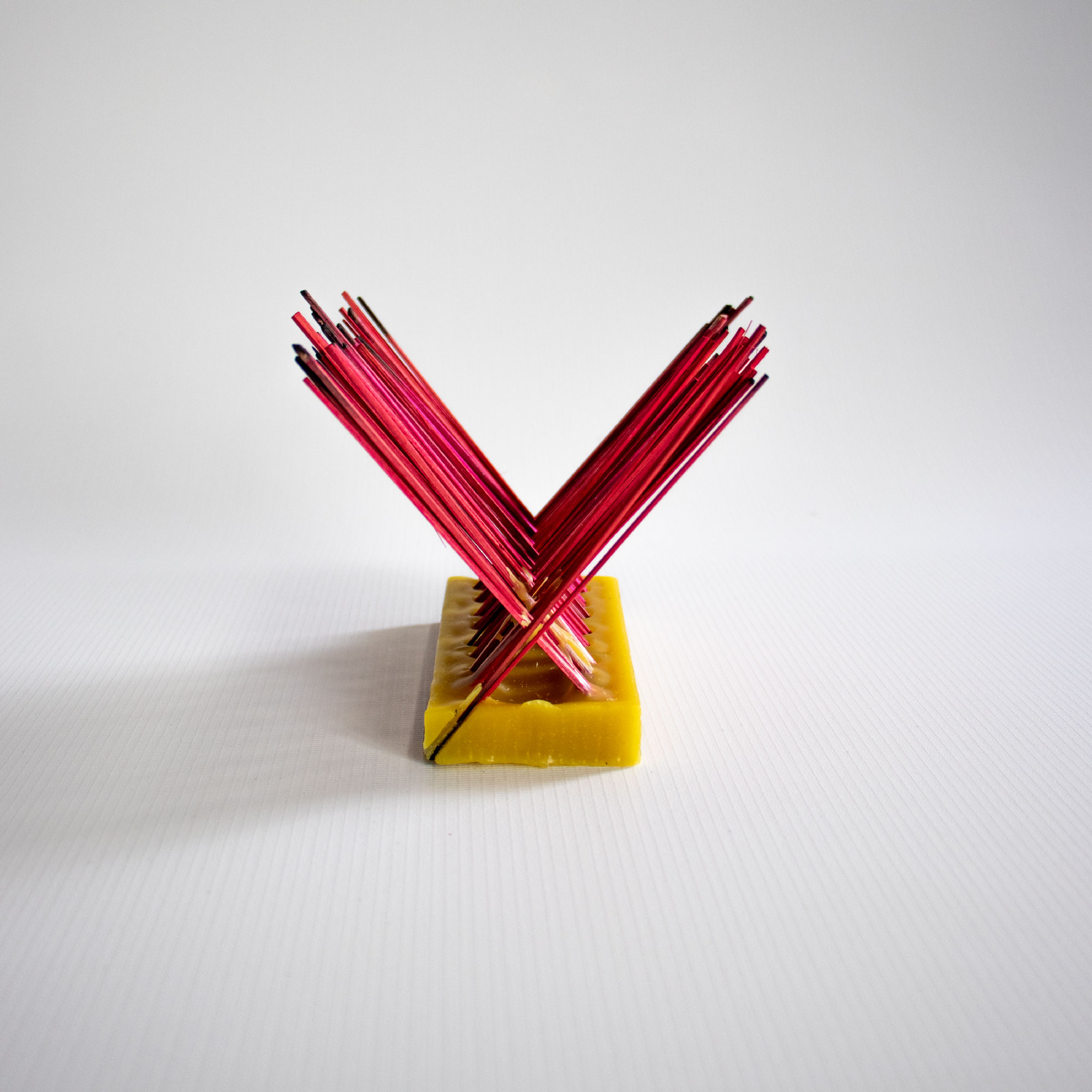

The path of Brunno Jahara is the recontextualization of very cheap pieces in plastic or clay, industrially manufactured in large series. In that process of dislocation and regrouping, he generates new uses and, particularly, new meanings. These are ready-made objects.

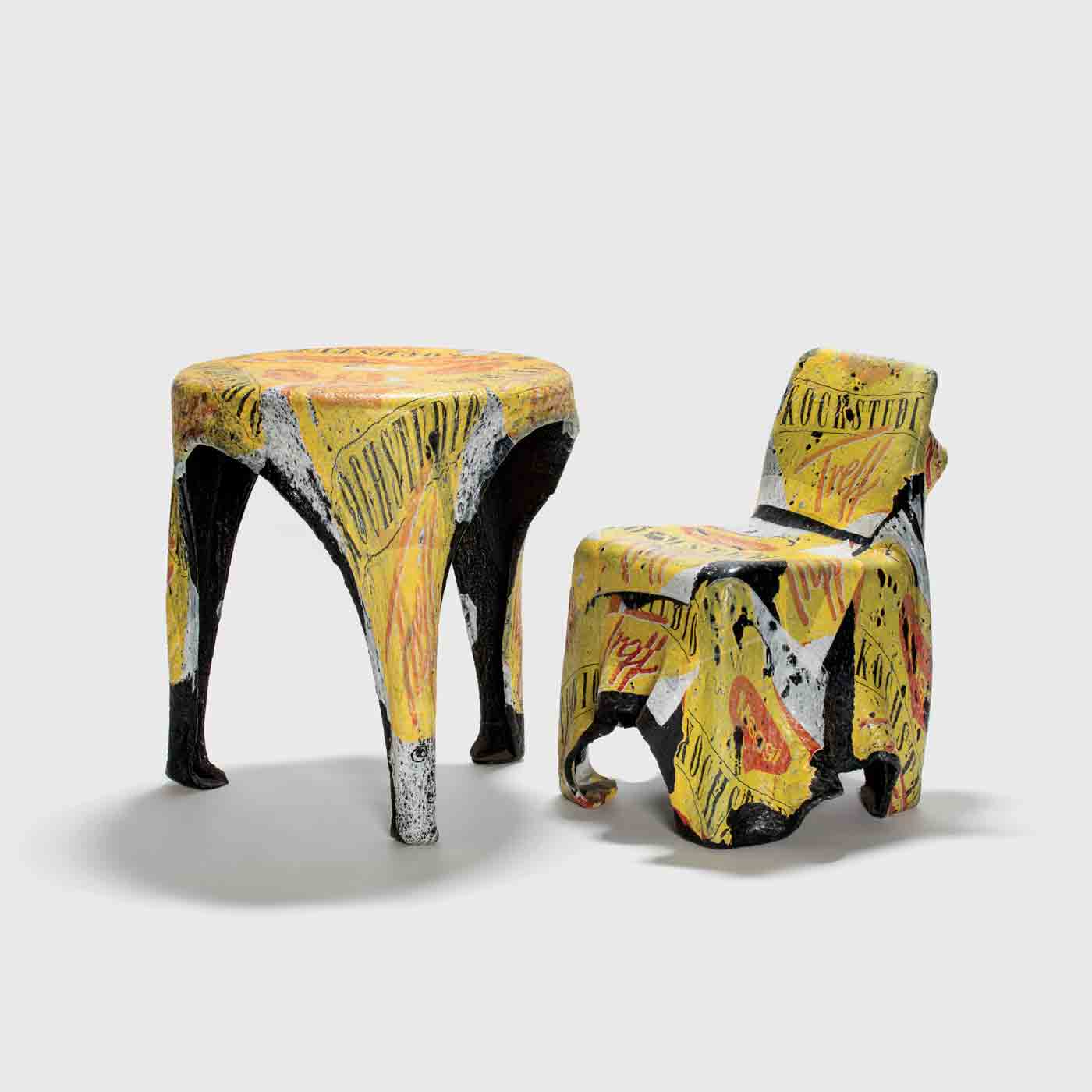

Curator Luján Cambariere, on the other hand, in her Colectivo Ático de Diseño, starts with antiquities and invites designers to recreate the pieces, inserting them in new repertoires.

None of these three designers hide the genesis of their objects, but they do not make them evident either. Their objects do not intend to be manifestoes or statements; they are not loud. All of them display great ability to transform their environment through economical methods and resources. Further, they display inventiveness and an ability to offer solutions, even when they are far from ideal conditions and far from technological sophistication. Form transcends function so that it can incorporate different functionalities. Jahara and Ático de Diseño manage resources like humour and irony well, while Tótora chooses very clear silent poetry.

All these objects invite us, as consumers, to combine consumption and community living with the pleasure of aesthetic joy and a desire for a better world.

1 Conscious, Simple – Consciously Simple. The Emergence of an Alternative Product Culture, Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen (ifa), Stuttgart 1998.

2 “Novos alquimistas,” in Consumo Cotidiano/Arte, São Paulo, Itaú Cultural, 1999.

EXHIBITS FROM LATIN AMERICA

WORLD TOUR STATIONS