CURATORS ESSAY

RECYCLEWALLAH:

THE INDIAN STORY

by divia patel

Divia Patel

London, United Kingdom

Pure Gold Curator for

South Asia

Divia Patel is a curator in the Asian Department of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. She specializes in contemporary art and design, popular culture and photography from South Asia. Her recent research has been on contemporary design from India, which resulted in the publication of her book India Contemporary Design: Fashion, Graphics, Interiors in 2014. She was co-curator of the V&A’s major exhibition The Fabric of India (2015–2016) with responsibility for the modern and contemporary content. She is one of three authors of The Fabric of India book (with Rosemary Crill and Stephen Cohen, 2015). Her focus on contemporary South Asia has led to significant acquisition of work by contemporary artists and designers for the V&A’s permanent collections. In her early career she curated the exhibition Cinema India: The Art of Bollywood (2002–2007) which toured nationally and internationally and won a BBC award for achievement in the arts. She has curated The Photographers’ Pilgrimage: Exploring Buddhist Sites (V&A, 2009), co-curated Indian Life and Landscape (2009–2010) which toured extensively in India, and curated M. F. Husain: Master of Modern Indian Painting (V&A, 2014). She has published on all of these subject areas. She is a trustee of the Nehru Trust for the Indian Collection at the V&A Museum.

RECYCLEWALLAH: THE INDIAN STORY by DIVIA PATEL

The story of recycling and repurposing in India takes us from the poorest in society to the luxury consumer. The materials, processes and products are wide-ranging and shaped by economic need, unskilled and skilled labour, as well as by creative impulses and experimentation.

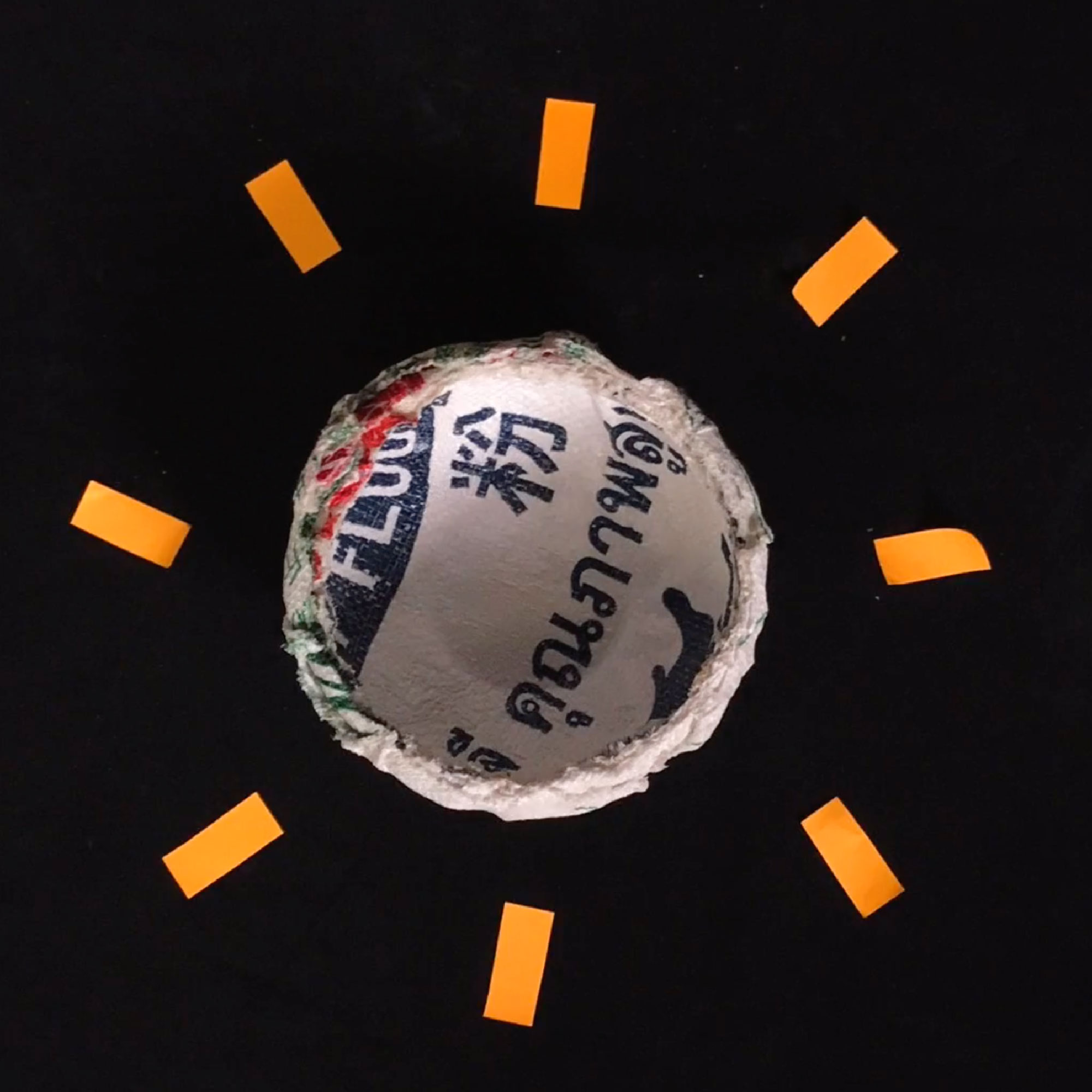

On the streets of India tin cans are made into oil lamps, bicycle parts become stools for local tea stalls and dried leaves are moulded into food containers for serving snacks. These are a few examples of jugaad, a Hindi term which means adapting or improvising what you have to create a solution. This is born of the “non-waste” mentality necessary for the poorest of society and is common to many developing nations. In recent years jugaad has been intellectualized as an approach whereby entrepreneurs are incentivized to develop products that utilize minimal resources in order to make them more affordable for larger sections of the population.[1]

Alongside jugaad, there is also a long tradition of repurposing everyday items by small traders who circulate in towns and villages, from street to street, calling out for local people to bring out their rubbish. Old newspapers are bought by the raddiwallah, electrical appliances by the kabadiwallah, and unwanted clothes are exchanged for steel utensils by the bartanwallah. They sell these on to buyers in other towns; the newspapers often being made into paper bags for use by other vendors and the clothes are either sold at market or to larger traders who sort them and sell them on for upcycling. There is money to be made in waste and the system is most ruthless when applied to rag pickers, often children, who scavenge for waste on rubbish tips to sell to scrap dealers, who in turn sell on in a chain which sees junk being extracted for raw materials and precious metals to be utilized in other industries. India’s largest slum, Dharavi in Mumbai, is today famous for the informal economies that recycle large proportions of domestic plastic and electronic waste.[2] The formal sector too has seen the rise of industries in plastic, electronic and textile waste. The latter has a well-documented process in which used clothing is turned into blankets for the lower middle classes.[3]

A markedly different story of recycling but perhaps one of the most celebrated in India is that of Nek Chand’s Rock Garden in Chandigarh, Punjab. This is a forty-acre landscape with waterfalls, sloping terraces and hundreds of sculptures of people and animals all made from bits of broken ceramic tiles, rocks, electronic components, rubble and other discarded junk from the rubbish dumps of the city. Nek Chand started this creative masterpiece in 1965, working initially in secret at night, as he was using private government land. When eventually he was discovered in 1975, the garden was considered special enough to remain. Chand was given a government salary to continue the project, which led to the setting up of a local network for the collection of discarded materials that could be used in the garden. Today, the site has several thousand sculptures and is a major tourist attraction alongside the modernist buildings of Le Corbusier.[4]

Within this broad context sit “designed” products directed to the more affluent consumer. This is a nascent field of creativity in which the few designers currently experimenting with waste materials work mainly on a commission basis to make bespoke pieces. The one overarching element that ties them together is the often labour-intensive nature of the making process for which skilled artisans are essential. Waste from the textile industry features in several of these projects and is a reflection of the importance of textiles production in India, which dates back four thousand years – from the handmade to machine manufactured through to today’s fast fashion.

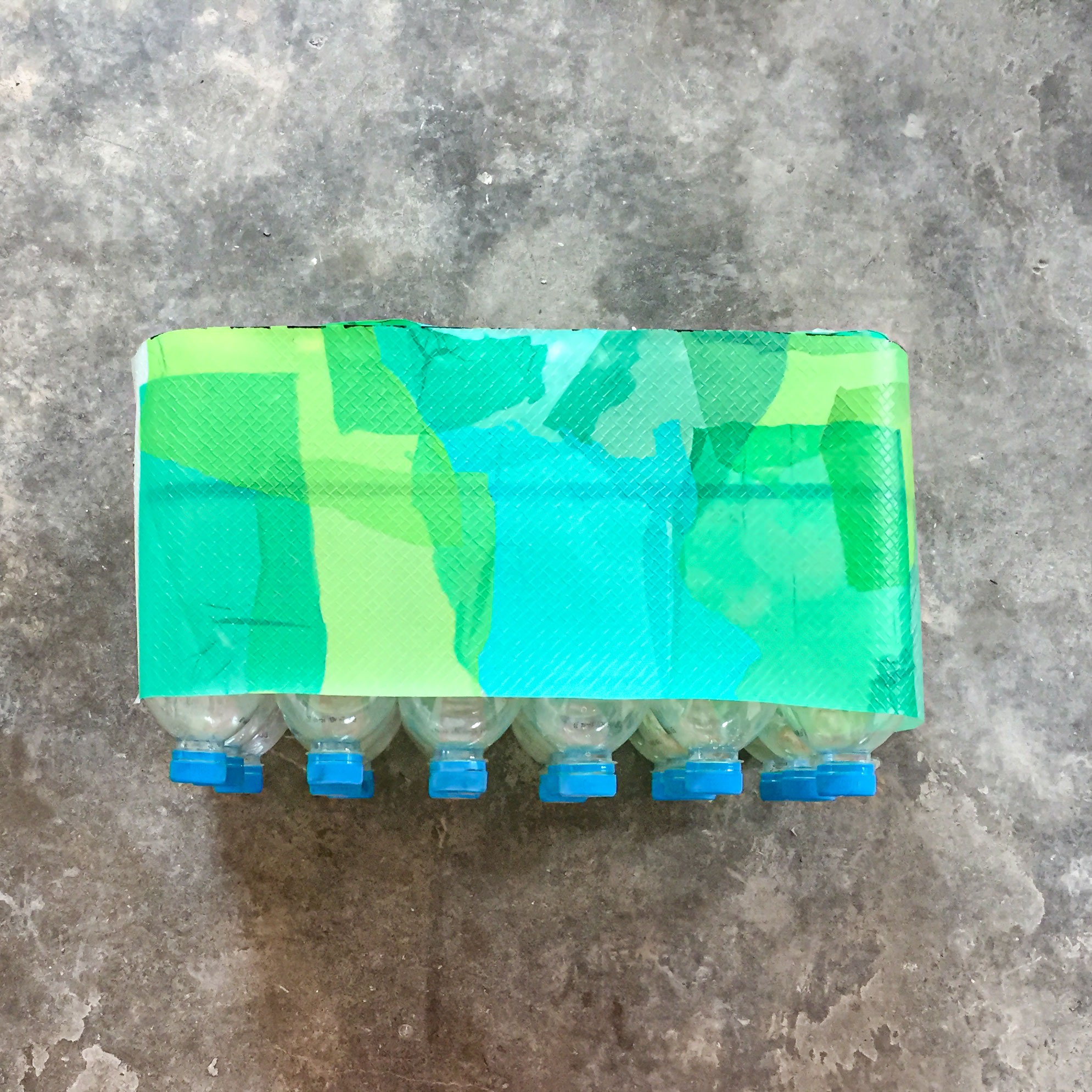

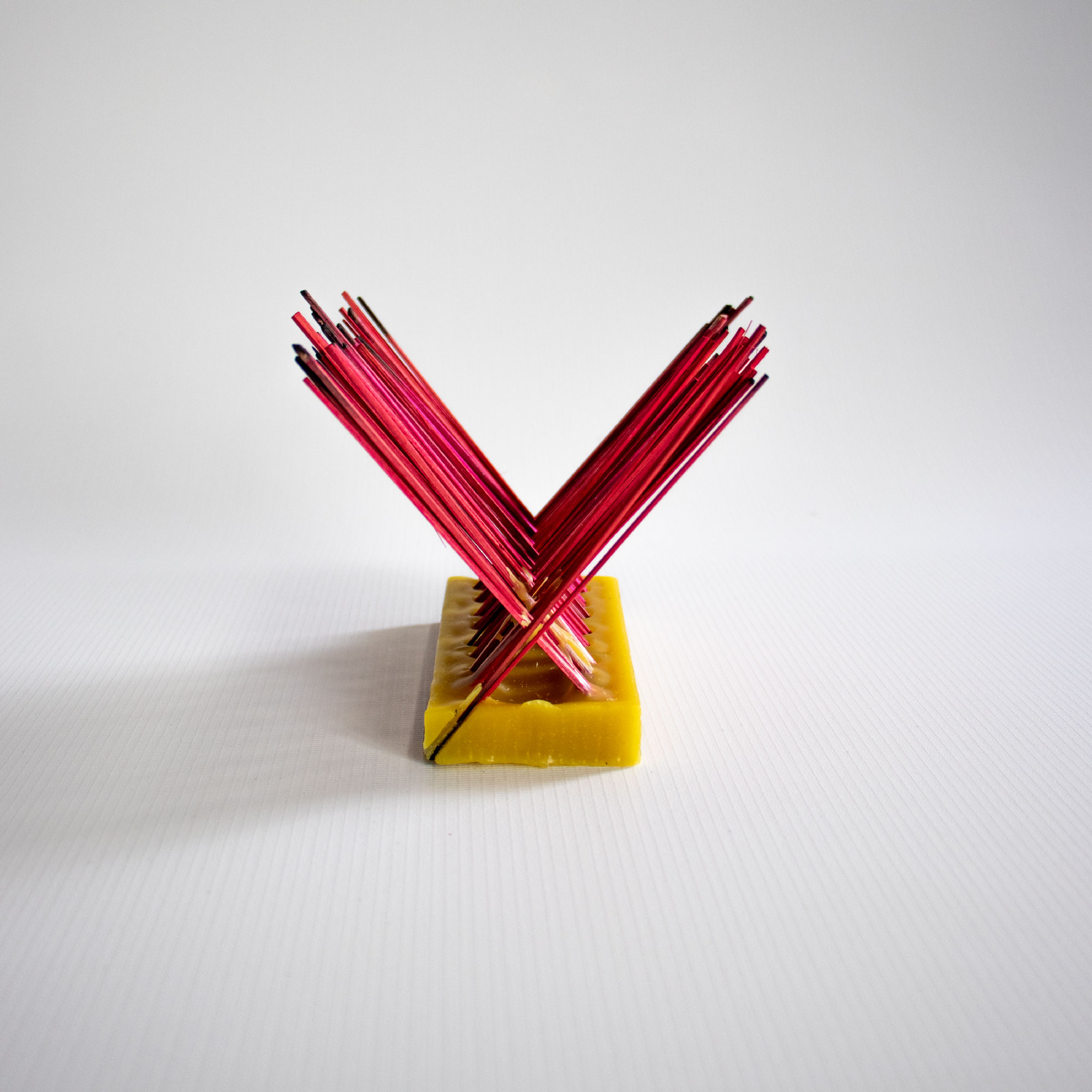

The Hindi word katran means piece or shred; katran rope is made from waste fabric often discarded by export houses or cloth mills. In the markets of Barmer, in Rajasthan, western India, these pieces are gathered in vast piles and sold as waste. They are collected and sorted by local farmers and spun into rope which is used by the local people as an alternative to jute or coir rope. This cheap colourful rope is often wound around a basic wooden frame to make a charpoy or day bed, which is a common piece of vernacular furniture seen across India. There is skill in the spinning of the rope and in the careful way in which patterns are woven into the charpoy. Mindful of this and using the same rope, Sahil and Sarthak Design Company have created a striking range of chairs for the modern urban middle-class home. Elegant iron frame structures are wrapped with the fabric ropes, customers can choose a range of colours and the texture of fabric (rough or smooth) that suit their interiors. The first chair was produced in 2008 to furnish a hotel and over the past six years versions of the katran range have travelled to homes across India and Europe. The designers are particularly sympathetic to local designs and have taken steps to document the process of recycling and rope making.[5]

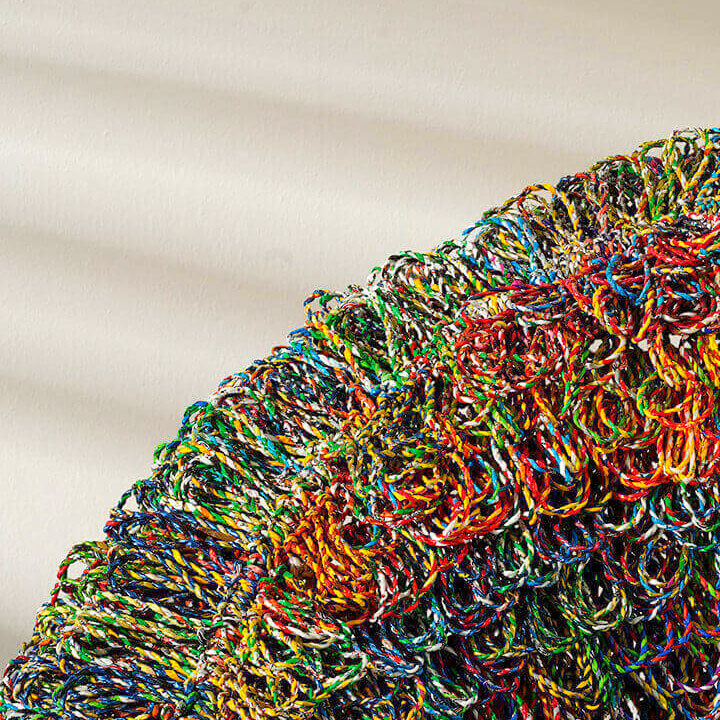

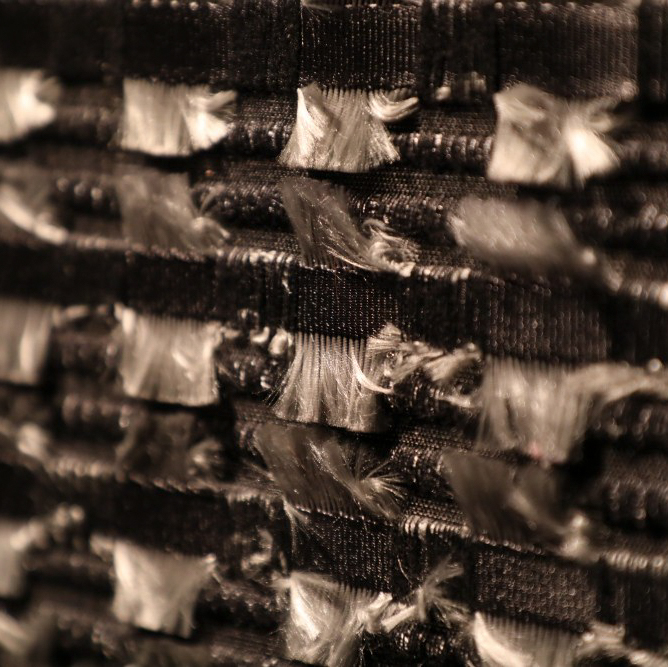

Utilizing a different type of textile is Studio Avni, based in Mumbai. They have devised a way of transforming unused saris into a range of irresistibly tactile and visually vibrant furniture. A universally recognized piece of Indian clothing for women, the sari is typically a single five-metre length of fabric draped around the body. Those worn for weddings or special occasions are made of brightly coloured silks woven with gold or silver thread decorative patterns and are often passed down as heirloom pieces from mother to daughter. However, some are sold to bartanwallahs and onwards to specialist buyers from where they are purchased by Studio Avni. The pompom pouf is one item in a range of furniture and appears to be made from hundreds of fabric balls stitched onto a fabric-covered stool. However, the method of construction is more complex and utilizes the structure of the sari to its best advantage. Keeping the sari as a whole, the undulating texture is made by sewing circles across the fabric, then gathering them to create pockets which are filled with foam. This is a labour-intensive skilled process and is reliant on the dexterity of the artisans at the studio. Functionality and practicality are inbuilt, making it possible to remove the cover and wash it if needed. The lustrous woven silk gives it a luxurious appeal. This range of stools includes the pagri, an experiment in imitating the pattern of the folded fabric when a turban is worn. Studio Avni offer a customization service that means that your favourite sari can get converted into a personalized piece of furniture.[6]

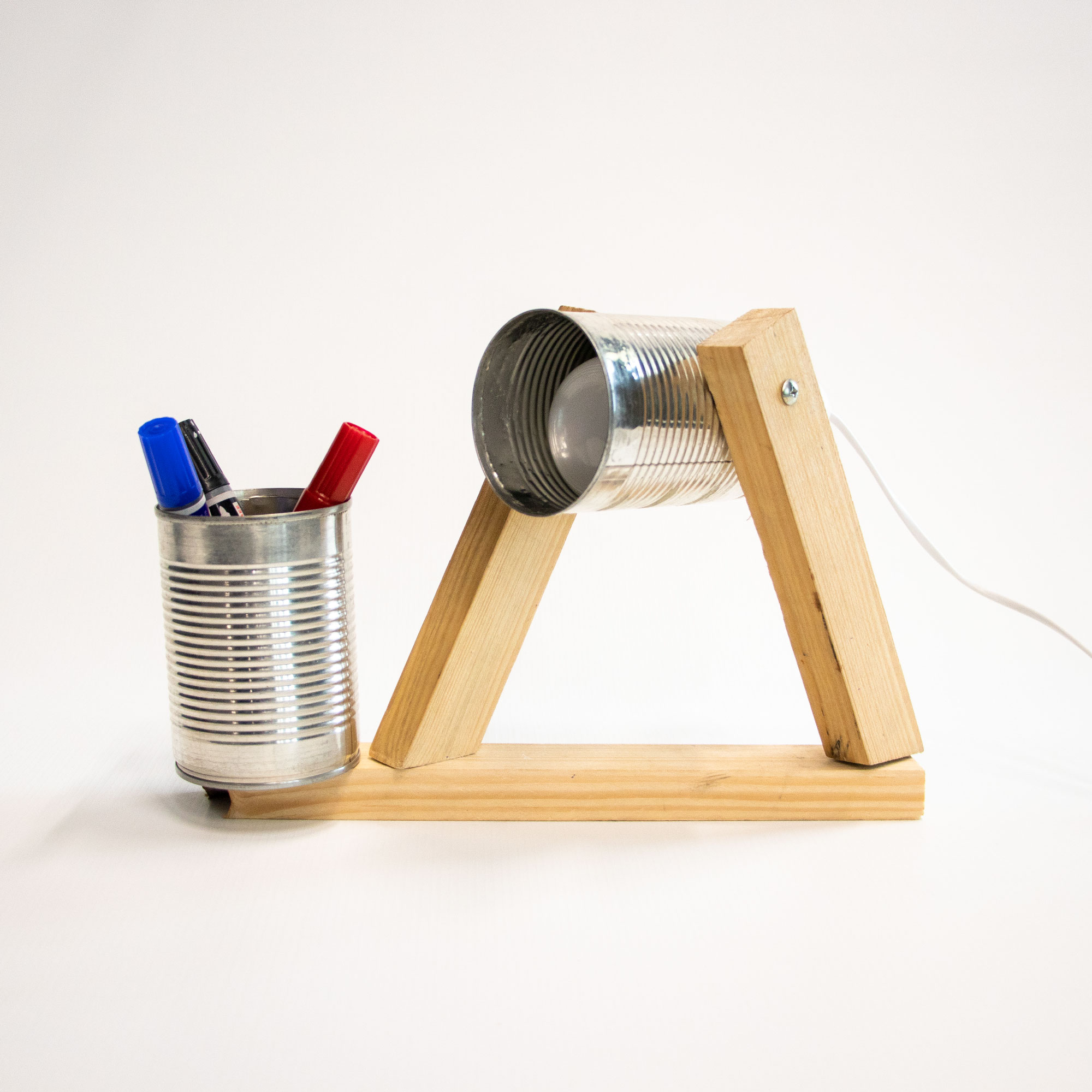

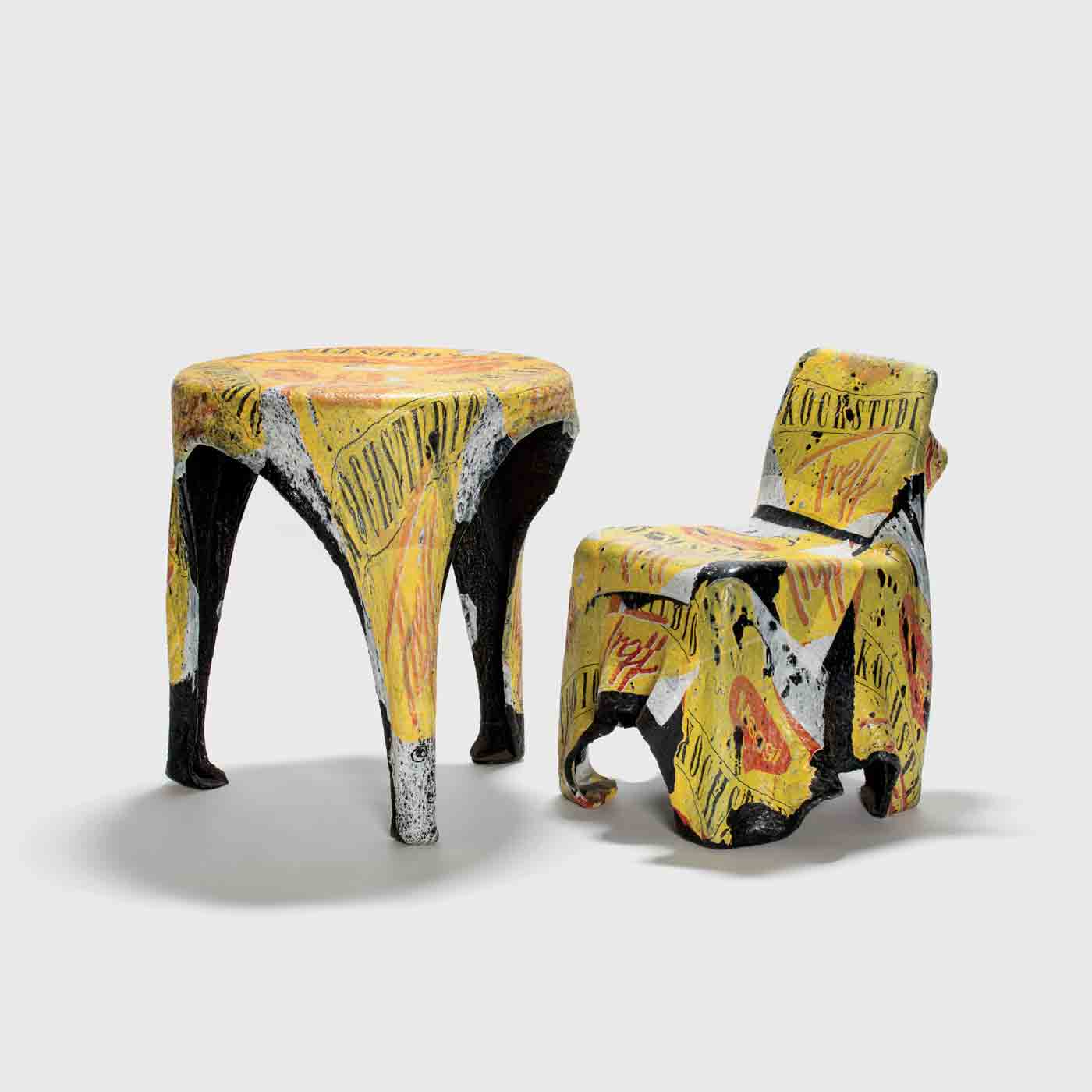

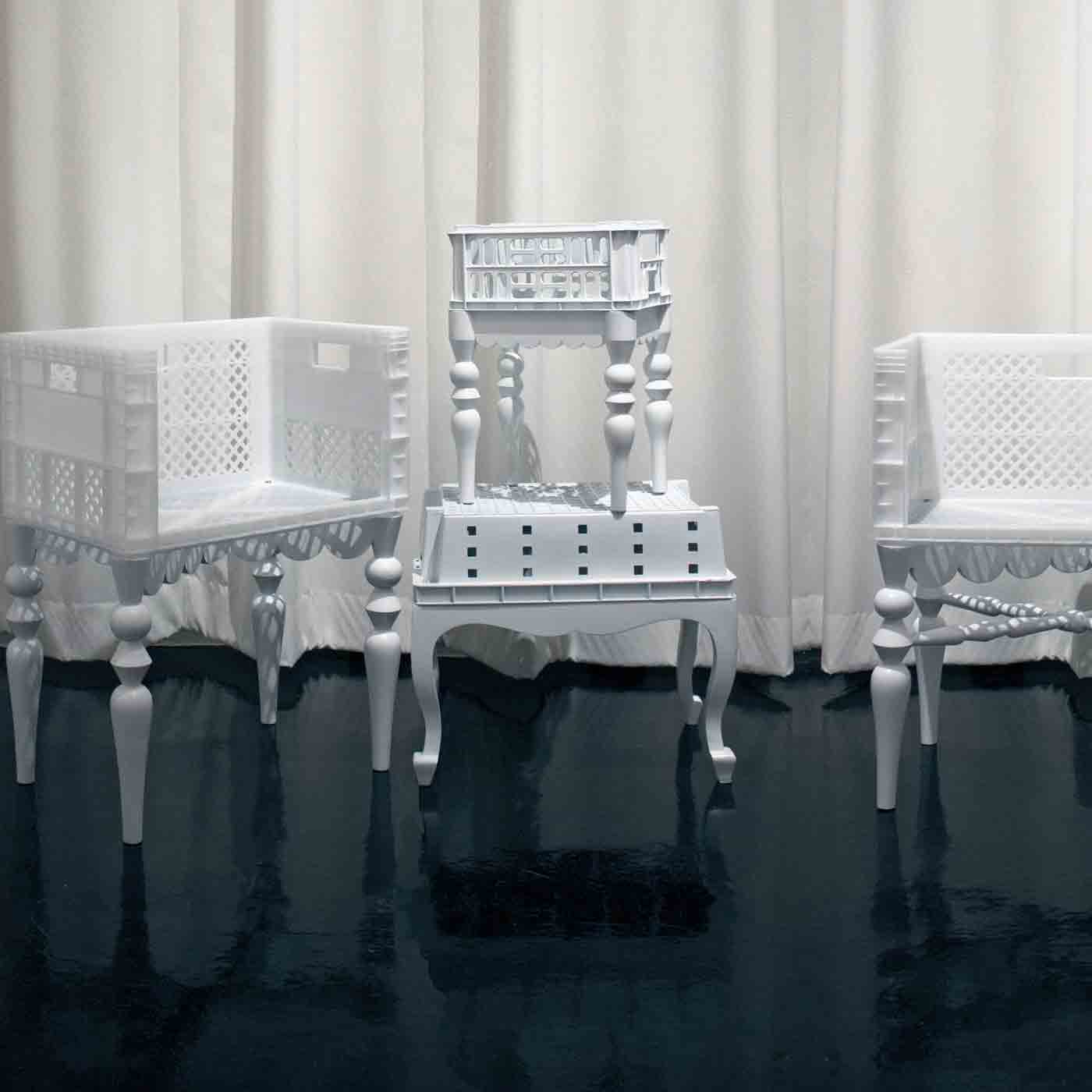

While most companies feature one or two pieces made from recycled material in their range, studio Alternatives is a rare example of a company that is entirely focused on upcycling. Using waste laminate and wood from architecture projects, motherboards from computers, as well as many other discarded materials, they produce small-scale household items and refurbish interiors. They have become specialists in converting used shipping containers into luxury living spaces. These are often commissioned by wealthy middle-class clients who own pieces of land on which they cannot get permission to build but on which they can park a container refurbished to their tastes. The bicycle rocking chair was one of Dhara Kabaria’s first experiments, which started as a student project. Initially envisioned as a sturdy item of outdoor furniture using the rubber tyres from a bicycle, this was later developed into an interior chair in which the old bicycle parts were given enhanced value though the process of cleaning them up, stripping them of paint and creating a form that has an almost sculptural presence when placed inside.[7]

Trying to make an impact on a different level is the French company Marron Rouge. Their production is a contribution towards alleviating poverty in India and they work with non-government organizations to make bags, accessories and small items of furniture from discarded bicycles tyres, seat belts made for vehicles, parachute bags recovered from the Indian Army, and the inner tubes of truck tyres which are collected by the poor in Delhi. The stools and lamps often have legs made from recovered wooden scaffolding from Indian building sites. These entirely handcrafted products offer employment opportunities for NGOs. As the products are sold online, the buyers are likely to be more global.[8]

Beyond furniture and household items, the fashion industry is also creating high-end pieces from recycled materials. Sabyasachi Mukherjee, a designer known for his incredible hand-crafted, highly embellished wedding outfits, has recently created a work for the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Made from old brocade saris overstitched with simple running stitch, the finished effect is one of opulence and fantasy. The overstitching is often referred to as kantha work, which references the historic kanthas famously made in the state of west Bengal and Bangladesh, whereby layers of old and worn cotton fabric are made into beautiful and functional bedcovers, mats or all-purpose wrappers.[9] Abraham & Thakore have stylish gowns embellished with oversized sequins made from discarded x-ray films. These have been sourced from hospital junk and are cut using die-moulds, a labour-intensive process.[10] Aneeth Arora and her label Péro offer an up-cycling service. Clients send her their favourite worn garments and she gives them a new look with her particular twist, using the offcuts from her own production. Denim jackets are relined with her familiar handloom fabrics, adding buttons, pockets, lace, ribbon, and fine embroidered detailing. The attention to detail and the price range are aimed at the affluent.

As India’s middle classes continue to rise in the post-liberalized economy so do their consumption habits. Dealing with the increasing amounts of waste created as a direct result of over-consumption is a major challenge, one which offers opportunities for new practical and inventive solutions.

1 Prabhu Jaideep, et al., Jugaad Innovation, Jossey Bass, California, 2012.

2 http://www.sustainablebusinesstoolkit.com/dharavi-indias-recycling-slumdog-entrepreneurs/ , http://qz.com/149632/the-indian-company-turning-e-waste-into-mounds-of-profit/ ,

http://www.businesstoday.in/magazine/features/companies-that-are-making-wealth-from-waste/story/195163.html

3 http://www.wornclothing.co.uk/projects/indian-shoddy-industry/ , Lucy Norris, Recycling Indian Clothing: Global Contexts of Reuse and Value, Bloomington, Indiana University

Press, 2010.

4 Iain Jack, “Politicised Territory: Nek Chand’s Rock Garden in Chandigarh”, in Global Built Environment Review, vol 2. no. 2, 2002, pp. 51–68.

5 Divia Patel, India: Contemporary Design: Fashion, Graphics, Interiors, New Delhi, Roli Books, 2014.

6 http://studioavni.com/about.html , Studio visit and interview by the author in March 2016. 7 Telephone interview with the designer in March 2016.

8 http://www.marronrouge.com

9 Divia Patel, “Textiles in the Modern World”, in Rosemary Crill, The Fabric of India, London, V&A Publishing, 2015, pp. 182–233.

10 Shefalee Vasudev, “Can Style and Recycling Meet?” in Livemint, April 18, 2015, http://www.livemint.com/Leisure/Rh1yODZclgZ6Zrgs4DaxwL/Can-style-and-recycling-meet.html

EXHIBITS FROM SOUTH ASIA

WORLD TOUR STATIONS

WORLD TOUR STATIONS