CURATORS ESSAY

TURNING WASTE INTO OPPORTUNITY

by tapiwa matsinde

Tapiwa Matsinde

London, United Kingdom

Pure Gold Curator for

Sub-Saharan Africa

Tapiwa Matsinde is a British-born designer, author, independent writer, professional blogger and creative consultant of Zimbabwean heritage. Educated in Harare, Zimbabwe, and the, she began her career in 1996 as a graphic designer and has since worked for leading international organizations in both countries. She is a graduate of the University for the Creative Arts, Epsom where she received a master’s of arts with distinction in design management focusing on creative enterprise.

Following a growing interest in contemporary design from and inspired by Africa, in 2010 she created the online platform Atelier Fifty-Five, a dynamic space to celebrate and showcase the work of talented designers and makers from across the African continent and those in the diaspora, aiming to encourage greater awareness of the continent’s growing design industries. She has written features about and interviewed some of the Africa’s leading creative practitioners. She also consults for a range of publications and organizations providing research, insight and product sourcing and other services.

Her first book, Contemporary Design Africa, was published in 2015 by the leading art book publishers Thames & Hudson, and shares the stories of over fifty designers and makers currently working on the African continent and beyond.

TURNING WASTE INTO OPPORTUNITY by TAPIWA MATSINDE

Taking an old, worn or unwanted object and repurposing it into something new – and, more importantly, functional – was, and still is, a prolific practice throughout the African continent. A culture of not wasting materials un necessarily, but instead finding a practical use for everything where possible served to minimize what would eventually end up being discarded. This practice stemmed from an inherent respect for the environment, which people relied on for food, water, shelter, clean air and clothing – all the basic essentials of life.

“Although people use and reuse everything there is not much organized recycling and upcycling in Mozambique yet. There are a few initiatives working on it but we definitely need more and I hope things will change in the coming years.”[1]

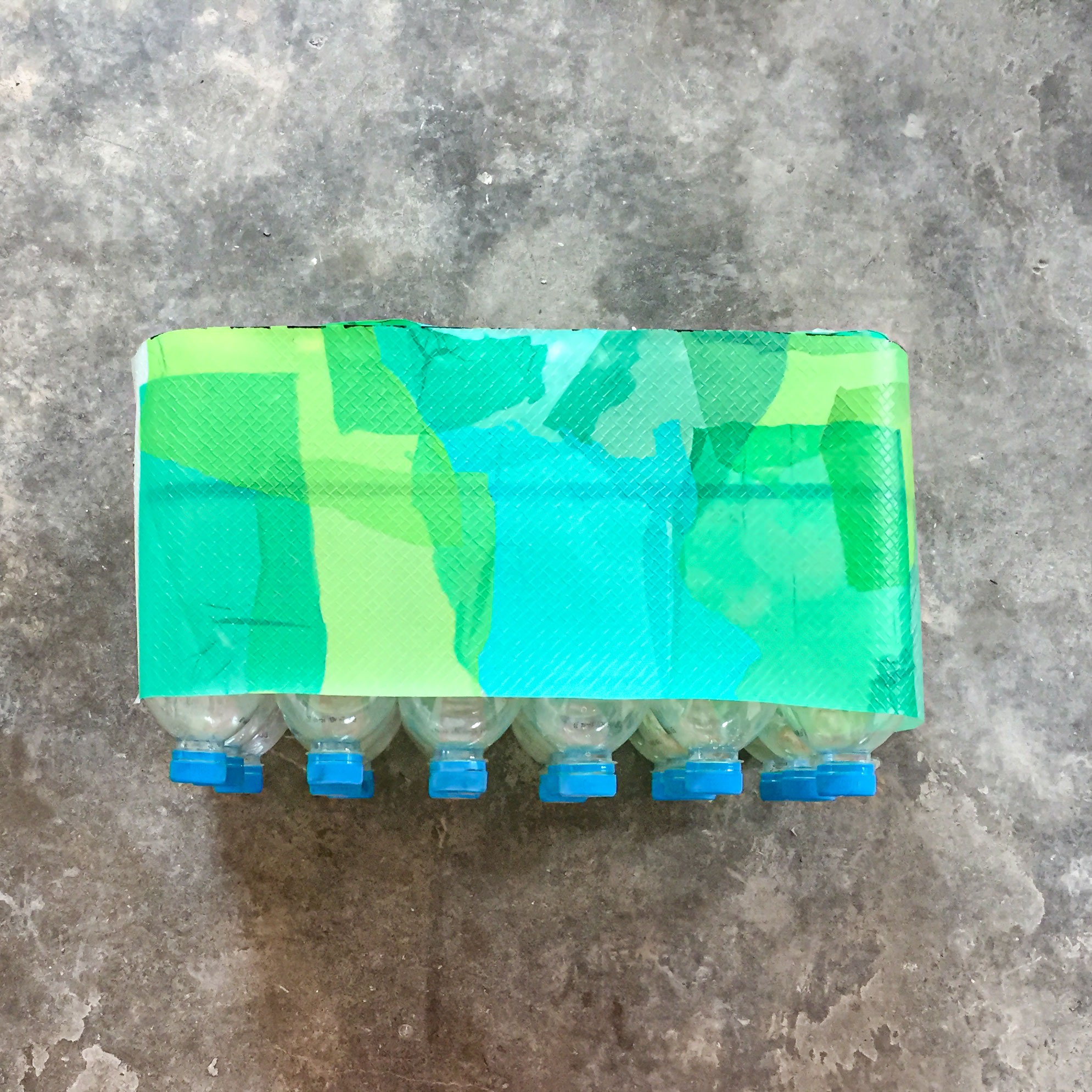

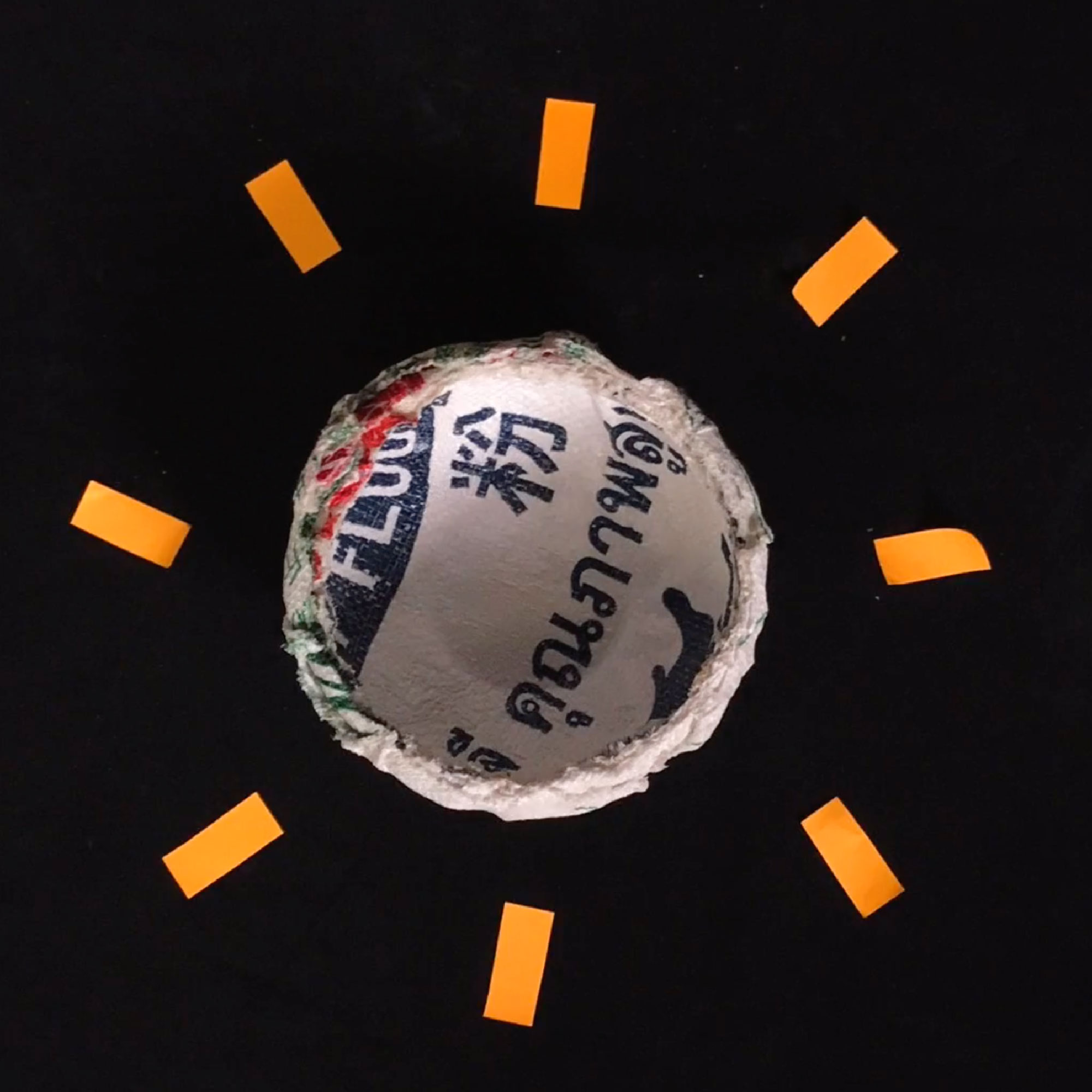

Though she refers to the nature of upycling in her own country, Mozambican artist Nelsa Guambe’s observations are reflective of similar situations in other African countries. Today, across the continent, people still continue to reuse, repurpose and repair things, with the continent’s artisans in particular leading the way, from whose makeshift workshops come forth products exhibiting remarkable resourcefulness and ingenuity. However, in line with changing cultural practices, repurposing materials and products is now primarily done of necessity, often related to the unavailability or expense of purchasing new or replacement materials or products. Despite this active upcycling culture, there has been an increase in mass consumption and the availability of products made with materials that can be cheaply and easily replaced and therefore discarded without much thought (such as plastic bags and bottles), and this has resulted in the accumulation of post-consumer waste. Today this is showing no sign of abating and is one of the biggest challenges many African countries currently face. As the Pure Gold exhibition highlights, the need for effective solutions to address the continuous accumulation of waste is not a problem confined to the African continent alone.

As the use and discard culture becomes more and more prevalent across Africa, compounded by factors ranging from a rapid increase in urban migration to cheap imports from countries such as China, parts of the continent are also having to deal with the effects of imported waste and toxic e-waste from wealthy nations around the world and sometimes illegally. All of these factors combine with inconsistent to non-existent and unregulated waste disposal systems, resulting in post-consumer waste often ending up in the streets – not so visible in affluent areas where municipal clean-up efforts tend to be concentrated. Or the waste is burnt – which is worse as it releases harmful toxins into the atmosphere; either way people and the environment are negatively impacted. In an attempt to tackle the issue, the past few years have seen several African governments passing legislation banning certain products – in particular plastic bags and second-hand clothing. Enforcement, however, is not always high on the agenda, leaving it up to enterprising individuals, private companies and community groups to devise their own solutions in response to the inefficiencies. Operating at grassroots level, organizations such as Wecyclers in Nigeria and the Njau Recycling and Income Generating Group in The Gambia are working to address the problem of waste in their local communities. They organize collections and either take on the task of correctly disposing of the waste themselves or pass it on to those who can do so or who are able to find constructive uses for it. These include designers, artisans and artists for whom discarded waste is a cheap, readily available source of material to work with, when compared to the availability or purchase cost of new unused raw materials.

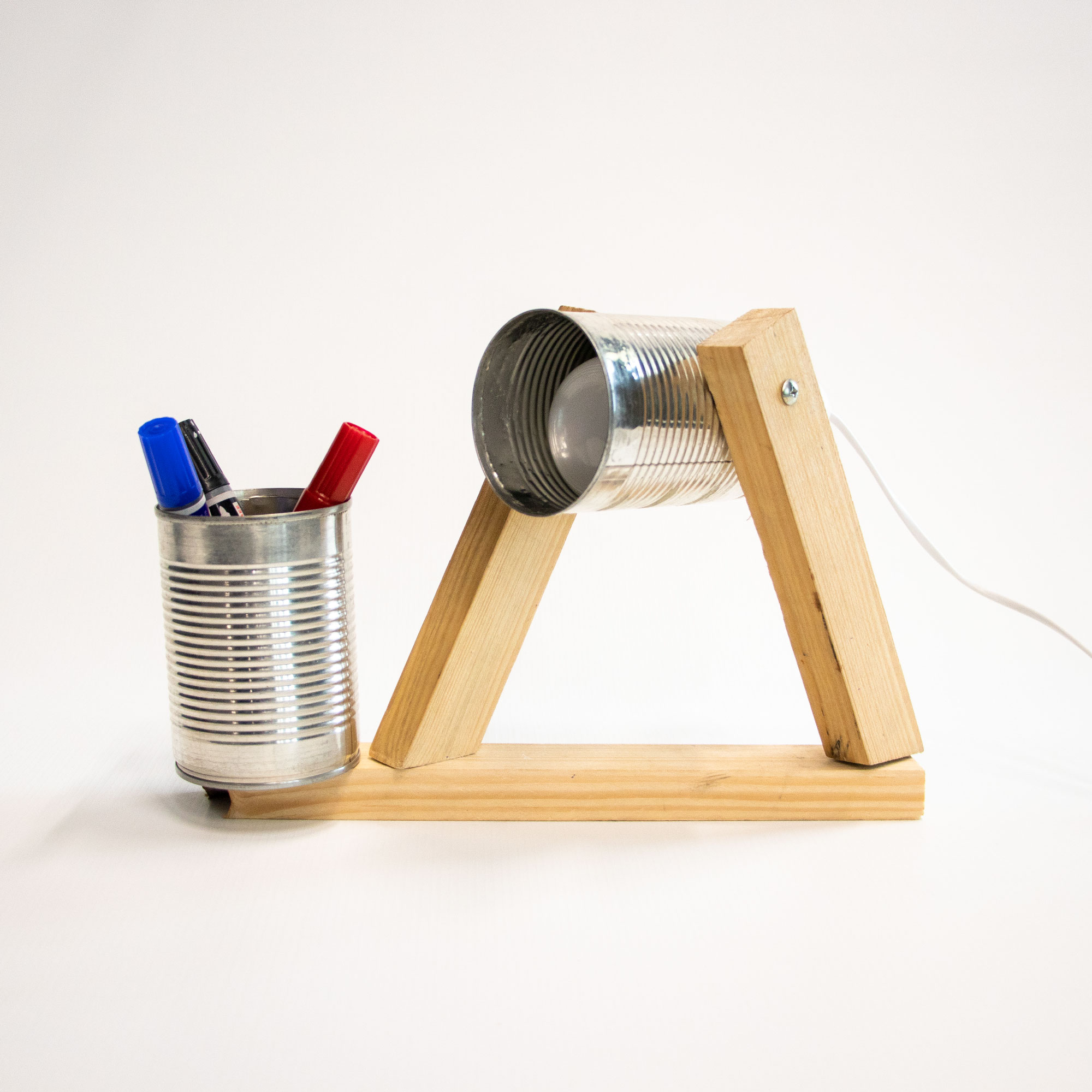

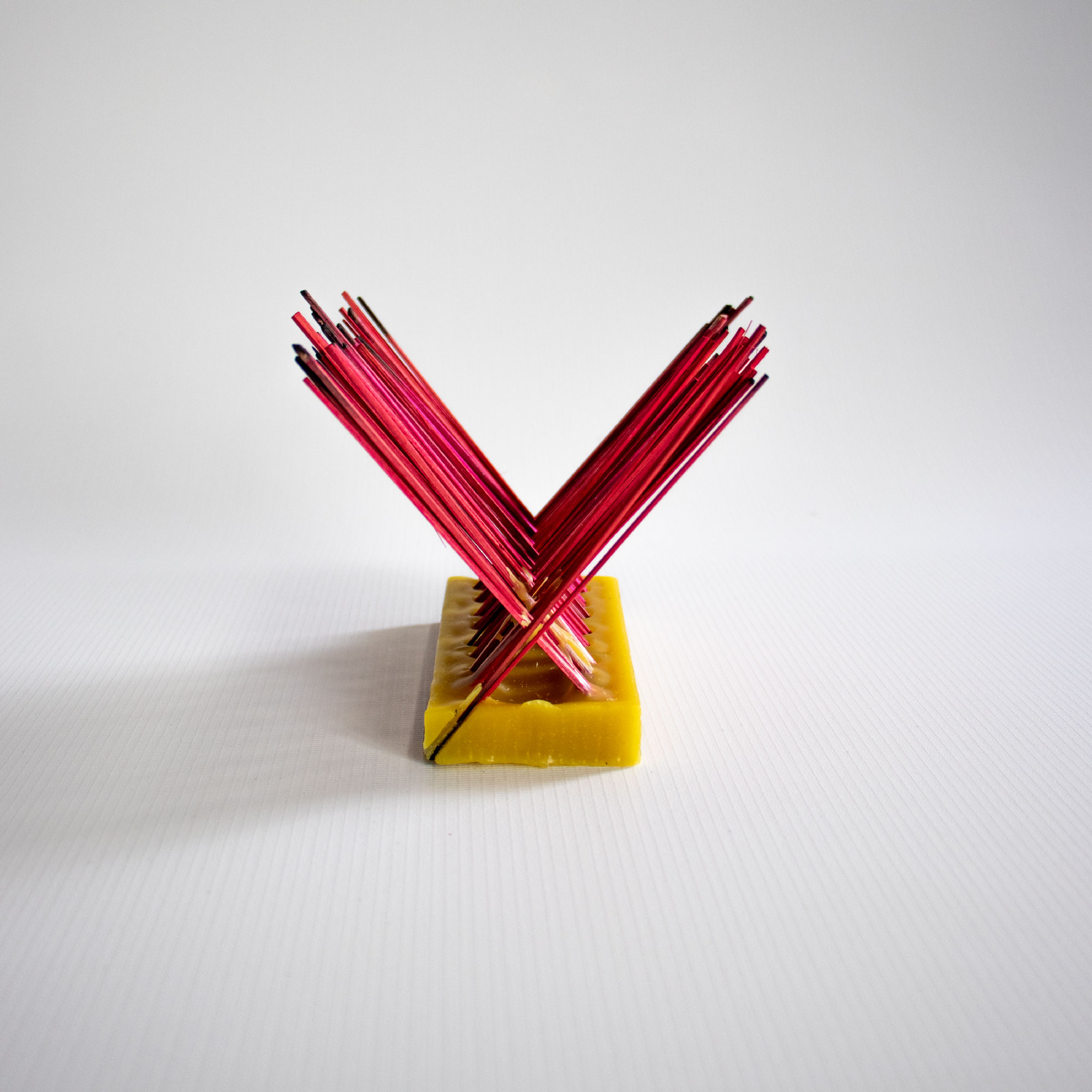

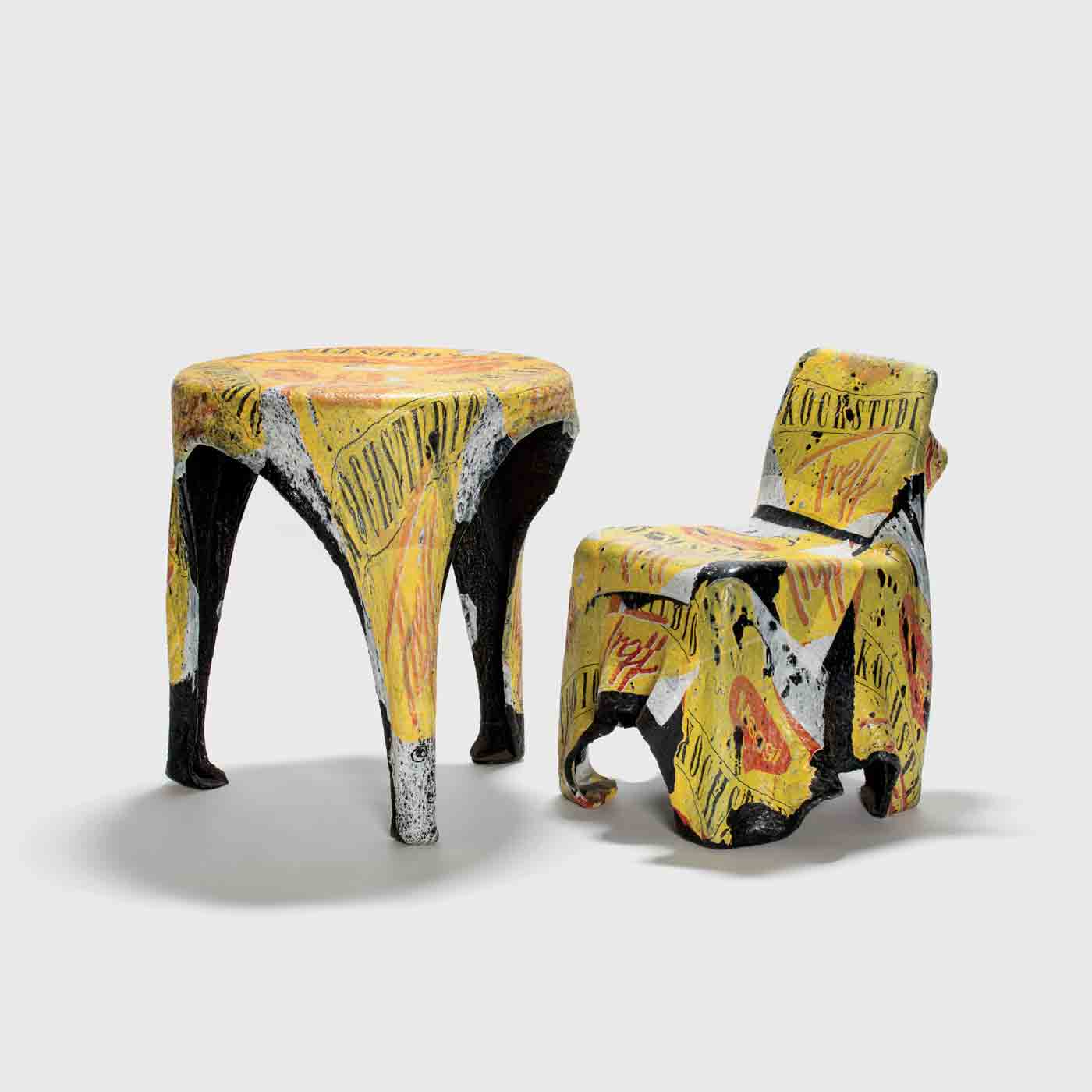

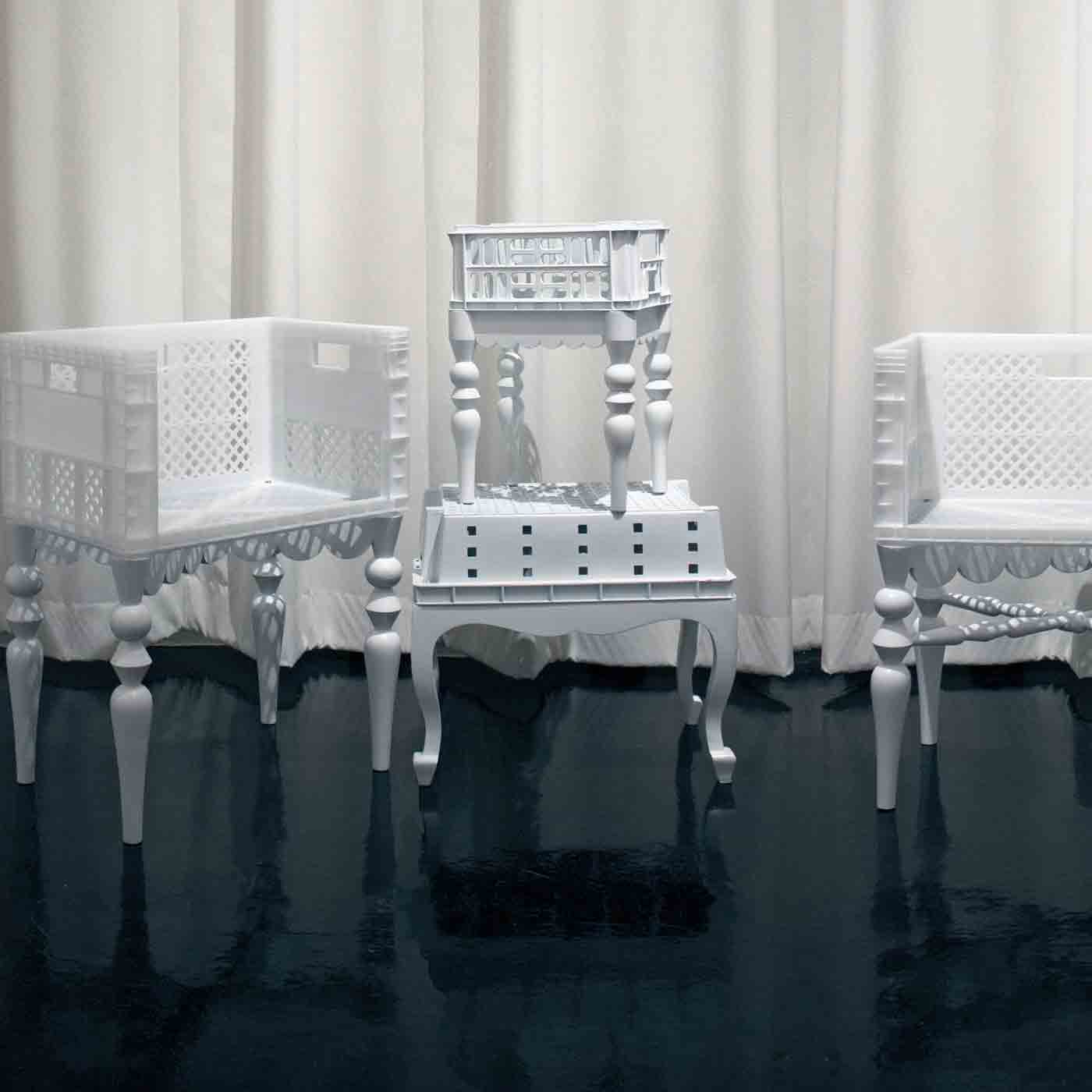

Importing or purchasing new unused raw material is often expensive and thus out of reach for many of the continent’s designers and artisans, who then face the prospect of either putting off their ideas until they can one day afford to make them work, or taking a proactive approach by improvising and working with what they have to hand. Those taking the latter approach have become renowned for finding value in materials rejected as being worthless. In their hands, discarded plastic, glass, metals, wood, bone, textiles, rubber and paper, the detritus of everyday life, are woven, polished, welded and remade into all manner of products from decorative accessories, to children‘s toys and household furniture items that are often infused with the unique stories of their past life. This is the case with Artlantique’s transformation of old decommissioned fishing boats, and Hamed Ouattara’s hammering and welding of discarded oil drums into distinctive furniture and product collections, reflecting, as Ouattara points out, “a truly local, innovative response to waste products.”[2]

“The raw material is the boat itself. Apart from the wood, it is also, on one hand the life of the boat and that of its master and family. The history of a livelihood. And on the other hand, the union of fishing and carpentry in Africa. Therefore the value is not only in the appearance but also in the history of each boat.”[3]

Artlantique and Studio Hamed Ouattara are just two examples highlighting a growing readiness among Africa’s contemporary designers and artisans to work with discarded materials to create sophisticated high-end products that have become sought after by discerning collectors across the globe. For a number of the continent’s prominent designers and artisans, achieving commercial success does not always see them leaving discarded materials behind – even though they are now more than likely to be in a position of being able to afford new unused raw material. Instead, they choose to further explore the possibilities, continuing to seek out discarded materials and in some instances going as far as to employ staff members specifically tasked with finding suitable materials in and around their cities and surrounding towns. This standpoint indicates the recognition of a greater responsibility that goes beyond making products and earning a living, using their work to call attention to and have a positive impact on prevailing social issues, including the detrimental effects of accumulating waste. The industrial designer Alafuro Sikoki-Coleman notes: “It just shows you how much we impact our environment, but also the other way around, how much impact our environment has on us. I think sometimes you don’t really notice your place in the world until you become more active in it or you make a conscious effort to change things.”[4]

Actively fostering and maintaining a productive and positive upcycling culture does more than just give a new lease of life to materials and products that have outgrown their original purpose. In echoing traditional cultural practices, with an instinctive pull towards being mindful of the space one inhabits, designers, artisans and creative organizations are mobilizing their local communities, and most notably extending a hand towards people living at the margins of society. When you bring people together conversations start, ideas flow and a common goal and a shared sense of purpose are found, leading to the creation of revenue streams, jobs, training and other community-enhancing opportunities. All the designs representing Africa in the Pure Gold exhibition are the result of actively engaging communities, adopting a practice that can be summed up by Ramón Llonch’s reflections on developing Artlantique: “Together we have created a wider scope for design, which has created strong social and cultural bonds.”[5] Based in Senegal, Artlantique has teams of master carpenters and artisans, many of whom take on apprentices in a bid to address local youth unemployment, as well as training the next generation of wood-workers to help keep local traditional skills alive. And, in Maputo in Mozambique, Piratas do Pau, the design studio that local artist Nelsa Guambe collaborates with, has established a dedicated upcycling centre working with discarded materials and training local young people in skills including carpentry and understanding the aesthetics of good design to enable them to create high-quality products.

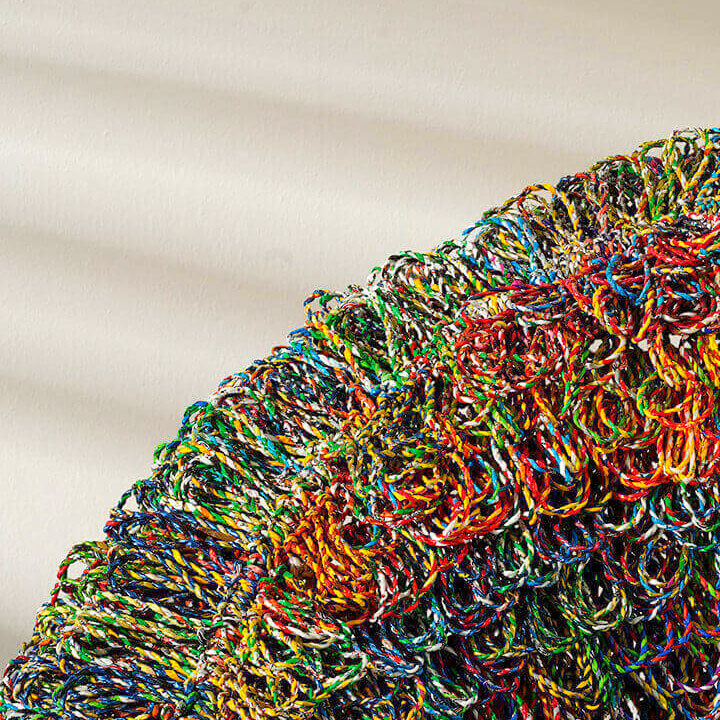

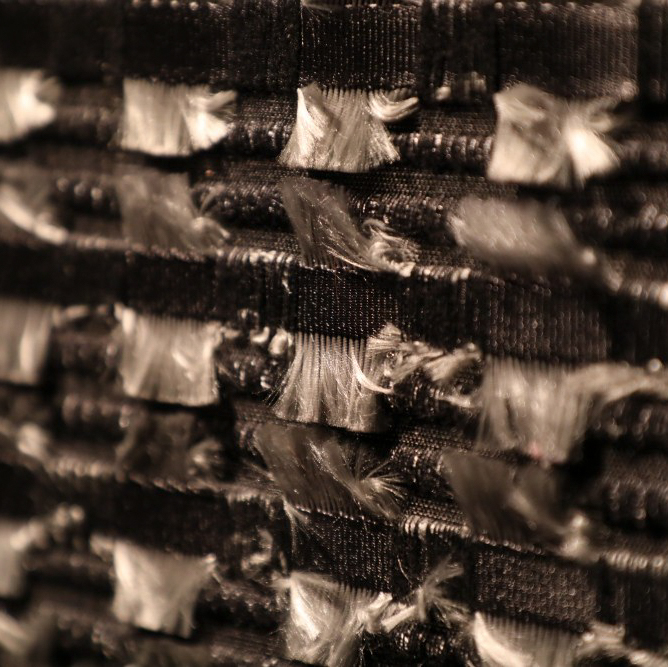

Upcycling is not just limited to discarded materials. In Nigeria, Alafuro Sikoki-Coleman is taking a destructive plant species and together with an island community in the Niger Delta is finding ways of turning it from a negative into a viable cash crop that provides a much needed revenue stream. By processing the plant into a pliable material that has the potential to be applied to a variety of uses from furniture (as currently used) to clothing, and with its biodegradable properties making it ideal for use as agricultural compost, Sikoki-Coleman is working towards the long-term sustainable goal of creating a clean, zero-waste industry benefitting both the community and the environment.

“For me it’s about us being more conscious of our choices and our actions, and also how everything is interlinked.”[6]

Granted, there is more to Africa’s designers and artisans than just being known for working with discarded materials, but the level of ingenuity and innovation now applied to working with waste is commanding increasing global attention, and contributing towards creating greater awareness for the need to consume less and upcycle more. Sustainable solutions continue to be needed to effectively address what is undoubtedly a pressing global issue.

1 Guambe, Nelsa: quotation from an interview with the artist

2 Ouattara, Hamed: quotation from www.studiohamedouattara.com

3 Artlantique: quotation from http://www.artlantique.com

4 Sikoki-Coleman, Alafuro: quotation from an interview with the designer

5 Artlantique: quotation from http://www.artlantique.com

6 Sikoki-Coleman, Alafuro: quotation from an interview with the designer

EXHIBITS FROM SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA

WORLD TOUR STATIONS

WORLD TOUR STATIONS