CURATORS ESSAY

PURE GOLD OR: WHY

IT IS WORTHWHILE

TO SOMETIMES PAY

MORE ATTENTION TO

DOMESTIC WASTE

by volker albus

Volker Albus

Karlsruhe, Germany

Pure Gold Curator for

Europe

Born in 1949, Volker Albus studied architecture at the RWTH Aachen University, Germany, from 1968 to 1976 and then worked as a freelance architect. In 1984 he began to design furniture and to work in interior design. He quickly became one of the most important representatives of New German Design. He has written many books and also regularly publishes essays in magazines like Design Report, FORM, Hochparterre and KUNSTZEITUNG.

He has curated many exhibitions, including Gefühlscollagen – Wohnen von Sinnen (1986). For ifa (Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen) he has planned five touring exhibitions which he also curated long term. Since 1994 he has been professor of product design at the Karlsruhe University of Arts and Design, Germany.

PURE GOLD OR: WHY IT IS WORTHWHILE TO SOMETIMES PAY MORE ATTENTION TO WASTE by VOLKER ALBUS

“Bayern Munich are playing today in shirts made of rubbish.” This was a headline in the Bild newspaper in November 2016 for a pre-match report on the German football Bundesliga game between Bayern and 1899 Hoffenheim. Of course, this did not mean second-hand shirts from a collection of old clothes, but, as the report said, shirts made completely of “rubbish from the oceans” – “of 28 old plastic bottles that were fished out of the sea.” The report continued: “With these shirts, sports’ outfitter Adidas and the environmental campaigners Parley want to warn us about the pollution of the seas. Each year 20 million tons of plastic rubbish are thrown into the sea, and it takes a shocking 600 years for this to decompose.”[1]

Even if this initiative was not motivated solely by concern for the environment, and Adidas probably will have had important marketing interests too, this use of resources is one example for the increasingly dynamic development of recycling technologies, and also for the high levels of acceptance of and appreciation for widely available recycled products.

This was not always the case. It is not so long ago that the word recycling conjured up images of paper that had the colour of potato peelings, or shred ded street surfaces, seen as quick fixes or a form of replacement material that should never be used wherever any aesthetic standards needed to be taken into account. This has now fundamentally changed. Nearly every day, we can read about new innovative products made entirely of “upcycled” plastic, old jeans, porcelain, rubber, and many other materials – presented not just in the business news, but also under the heading of “research and technology”. This means that the products discussed are not all semi-manufactured or basic products like toilet paper or bricks [2], but also high-end articles in the furniture and textiles industries, products where both technical and aesthetic quality are decisive for commercial success.

Prototypes for this strategy would include Philippe Starck’s Hudson Chair and Herman Miller’s Aeron Chair. These two chairs, and many more recycled products, are based on reusing materials that have been used before to make more or less the same kind of product, and that are first returned to their original state as mash, liquid, powder or fibre, even if they will again become chairs in their new shape and form. In terms of the production process, therefore, these products are not very different from tried and tested grey-brown recycled paper; and yet the modern textiles of a sports’ outfitter and the simple office-use stationery from a paper mill are in fact worlds apart. Aesthetic enhancement is one key development and difference. At the Cebit computer and technology fair in 2017, the Japanese company Epson presented a piece of equipment that worked with the so-called PaperLab process. The first step is to shred printed “old” paper, and then the shredded paper that this produces is transformed into new paper at the rate of 720 sheets per hour, with almost no need for water.[3]

It can be fairly assumed that it will not be long before decentrally operating machines like this Epson will be applied to other fields and technologies of production within domestic households. One example is 3D printers, which are now widely used. They can be fed with sorted and finely ground (in our own homes) household goods, and then perform whatever domestic needs are at hand, from making spare parts to small repairs. The necessary programming skills will not be a problem, as Generation Minecraft already has these today.

But we have not yet come quite so far. At present, these recycling technologies are still used centrally or at least within the spheres of influence of the companies that make these goods (Adidas, Emeco, Herman Miller, Epson). This in turn means that access is relatively limited and usually quite expensive. Just how expensive the use of this kind of process can be and how that will influence end-user prices, is shown in the case of an attempt to use recycling to transform one of the most significant “environmental polluters” of recent decades into an environmentally friendly product. The company Original Food, based in Freiburg, Germany, wanted to produce compostable coffee capsules as an alternative to the Nespresso version with high aluminium content that has led to around 4,000 tons of capsule trash each year.[4] This Original Food initiative sounds like a piece of good news, but the problem is that the price of the environmentally friendly capsule is 20 per cent higher than Nestlé’s product – and also lacks the clout of the “womanizer” George Clooney. Launching a new product could be simpler.

Difficulties notwithstanding, these examples show that, given the right technological adaptations and equipment, change is possible, while current developments and increasing acceptance mean that sooner or later processes like these will transform the principle of reuse into one – if not the – standard in raw materials acquisition.

It is true that political and financial programmes develop the greatest force of change in this field – and not the great ideas that designers have. In the examples of football shirts, furniture or coffee capsules made of recycled materials given here, the products are substitutes that look just like the “ecologically incorrect” products, with the exception of a hardly noticeable or invisible composition of materials. In other words, the success of these products is based only on a political and moral idea, or an economic or regulatory framework.

This is very different in the case of products that rework used and worn relatively cheap objects from everyday life “as found” materials. These products do not return recycled objects by means of technical processes to their original material form so as to make another entirely “new” product. Instead they leave the found materials more or less as found – in their final and specific material and formal composition as a product. Even if this strategy does not perfectly match the definition of the German Waste Management Act [5], or, put another way, does not correspond to our understanding of the recycling process, this form of reuse is nonetheless a very attractive alternative to the industrial “procurement of secondary materials” – at least from the perspective of design.

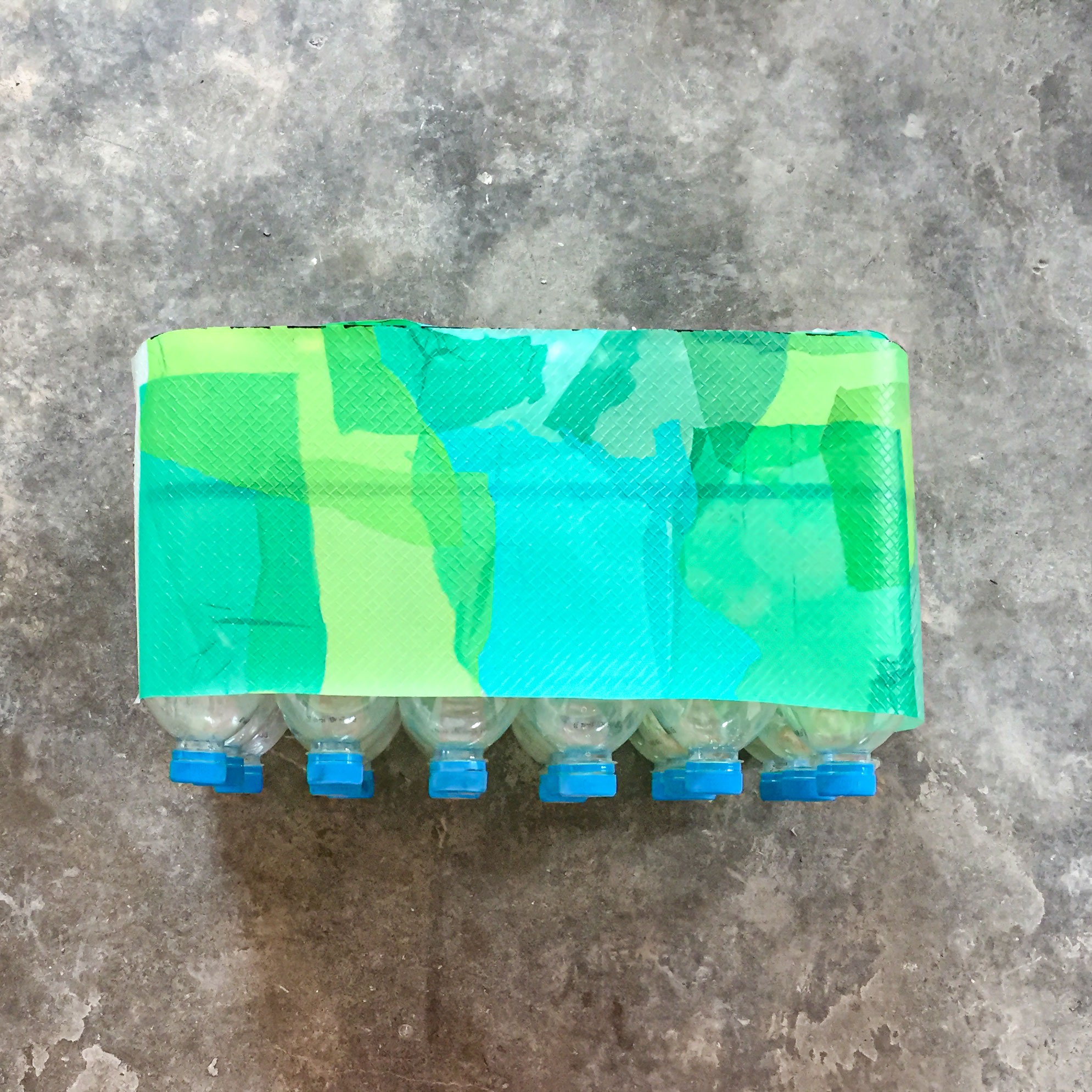

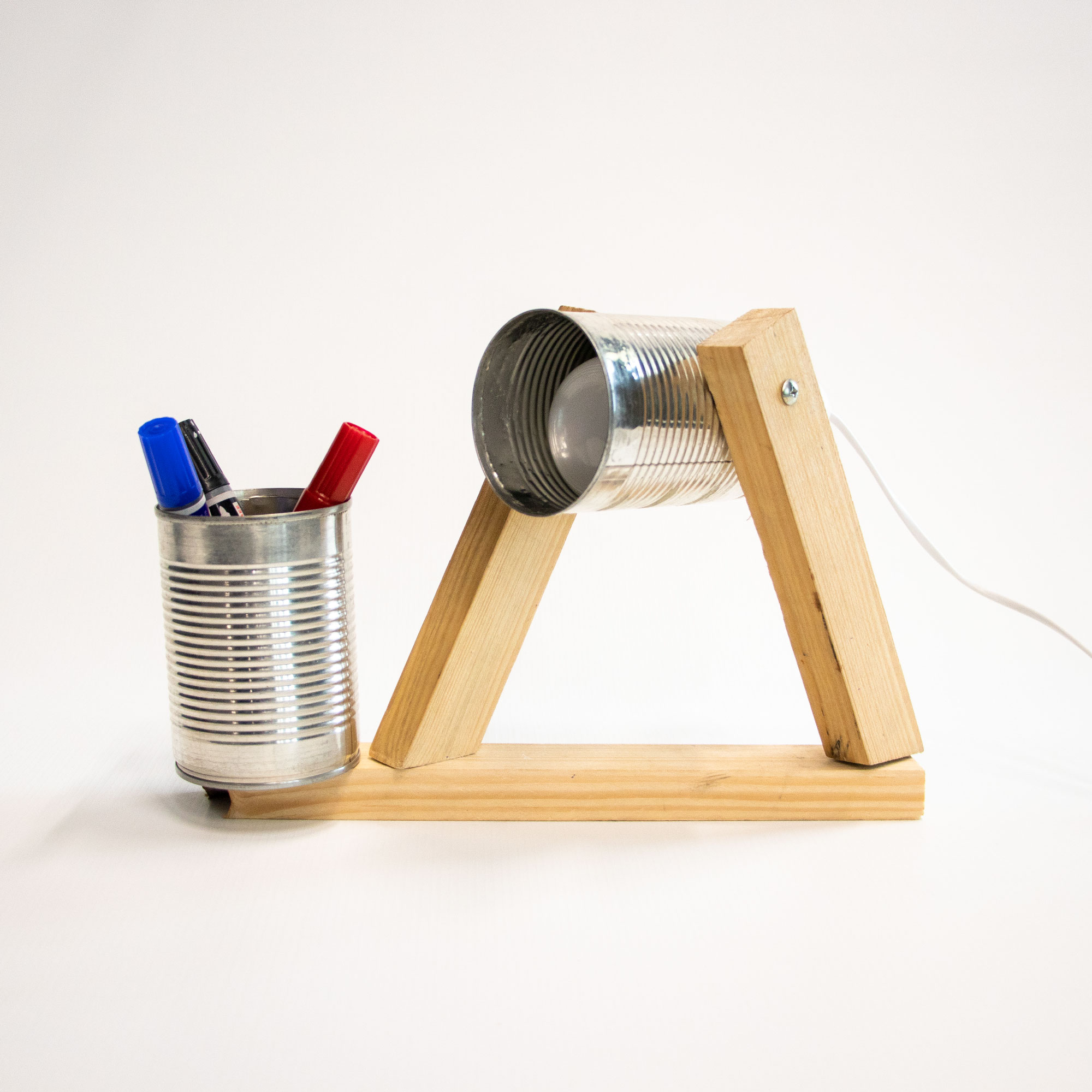

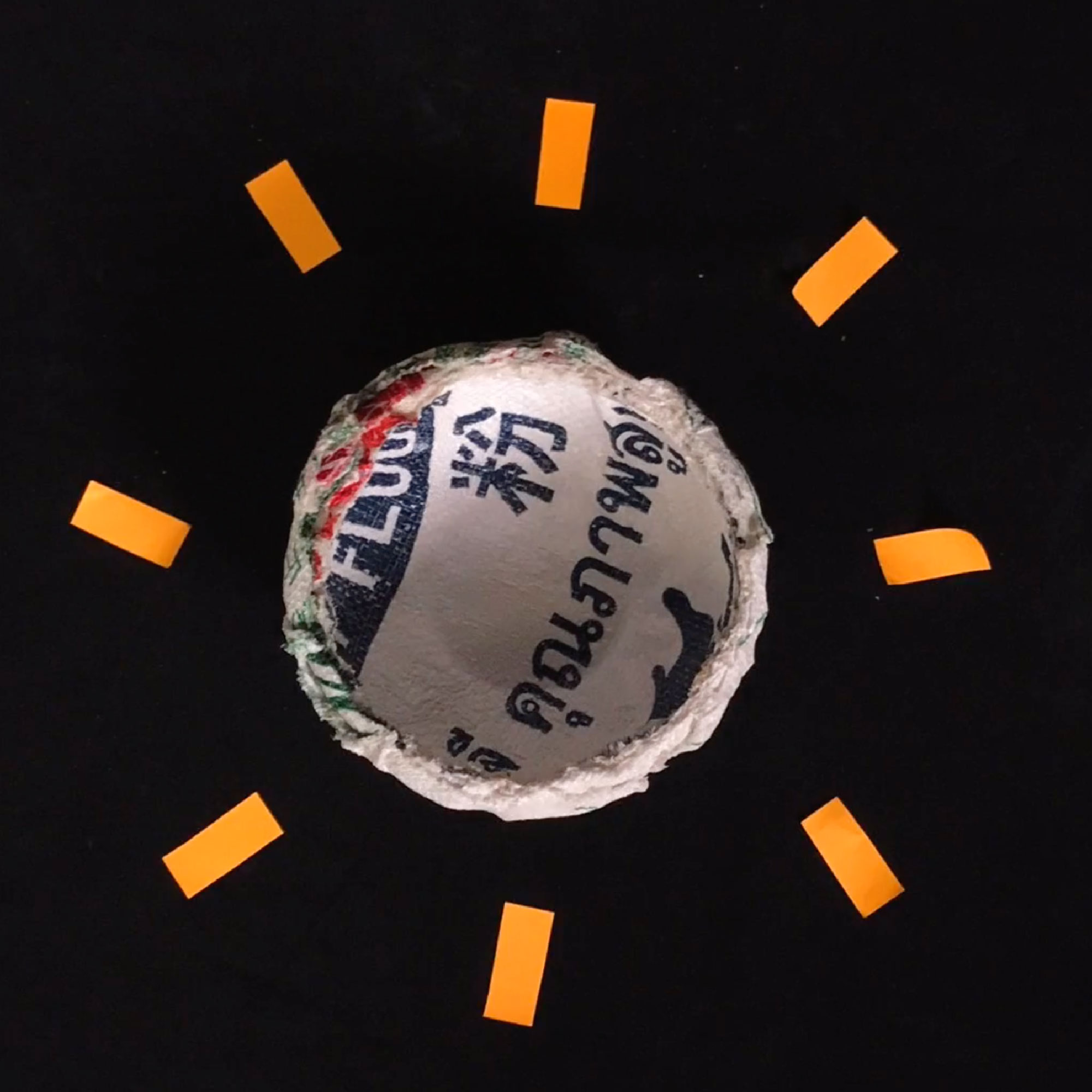

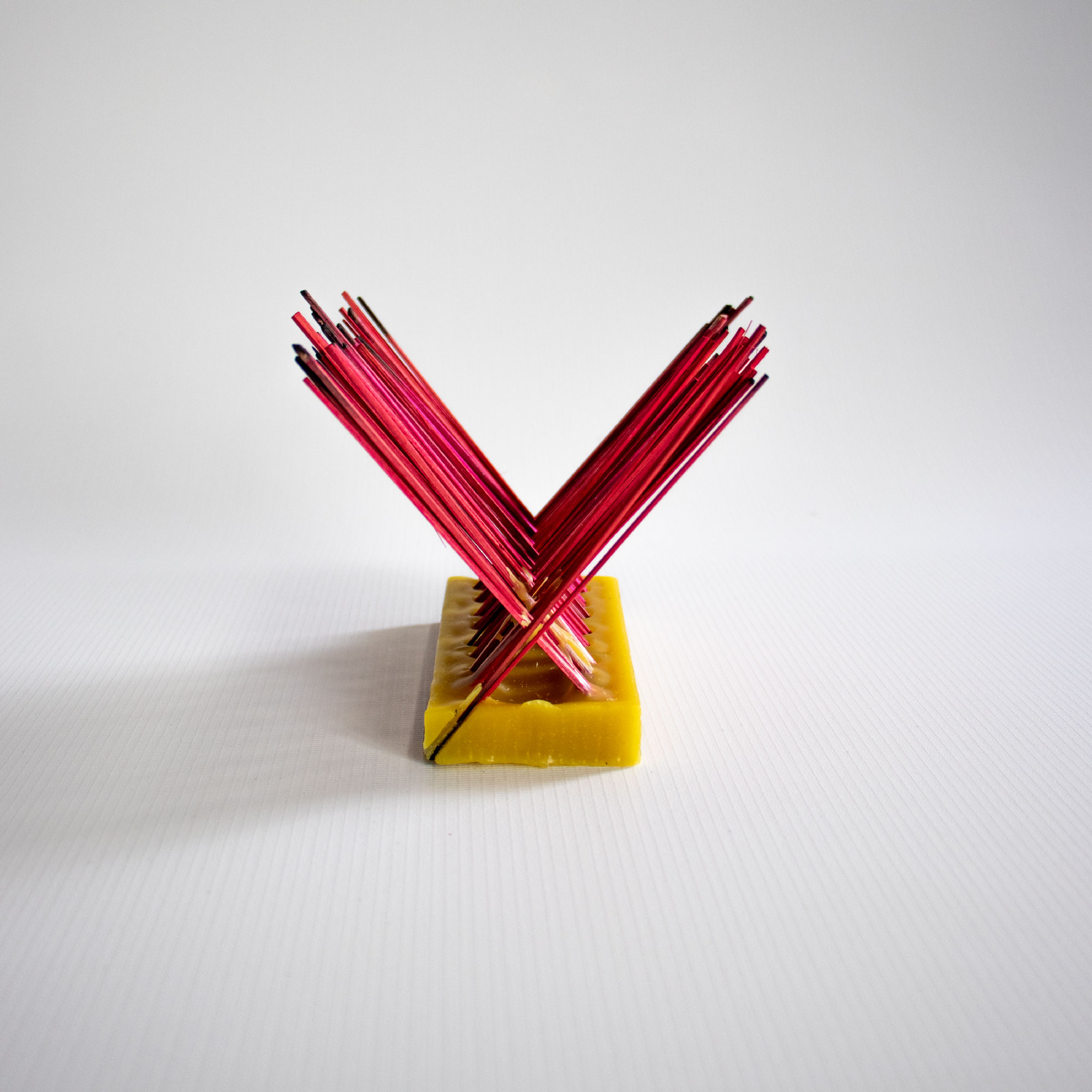

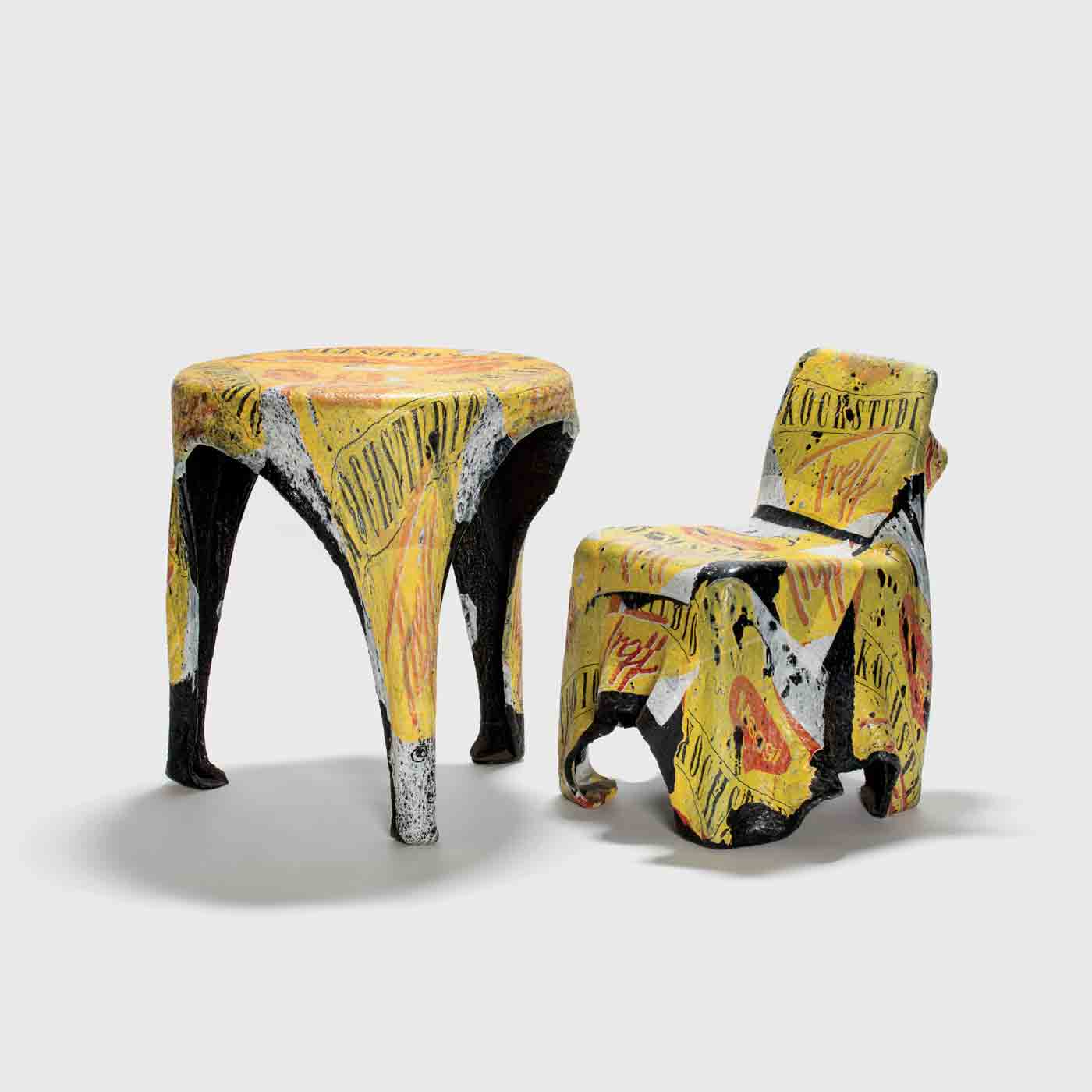

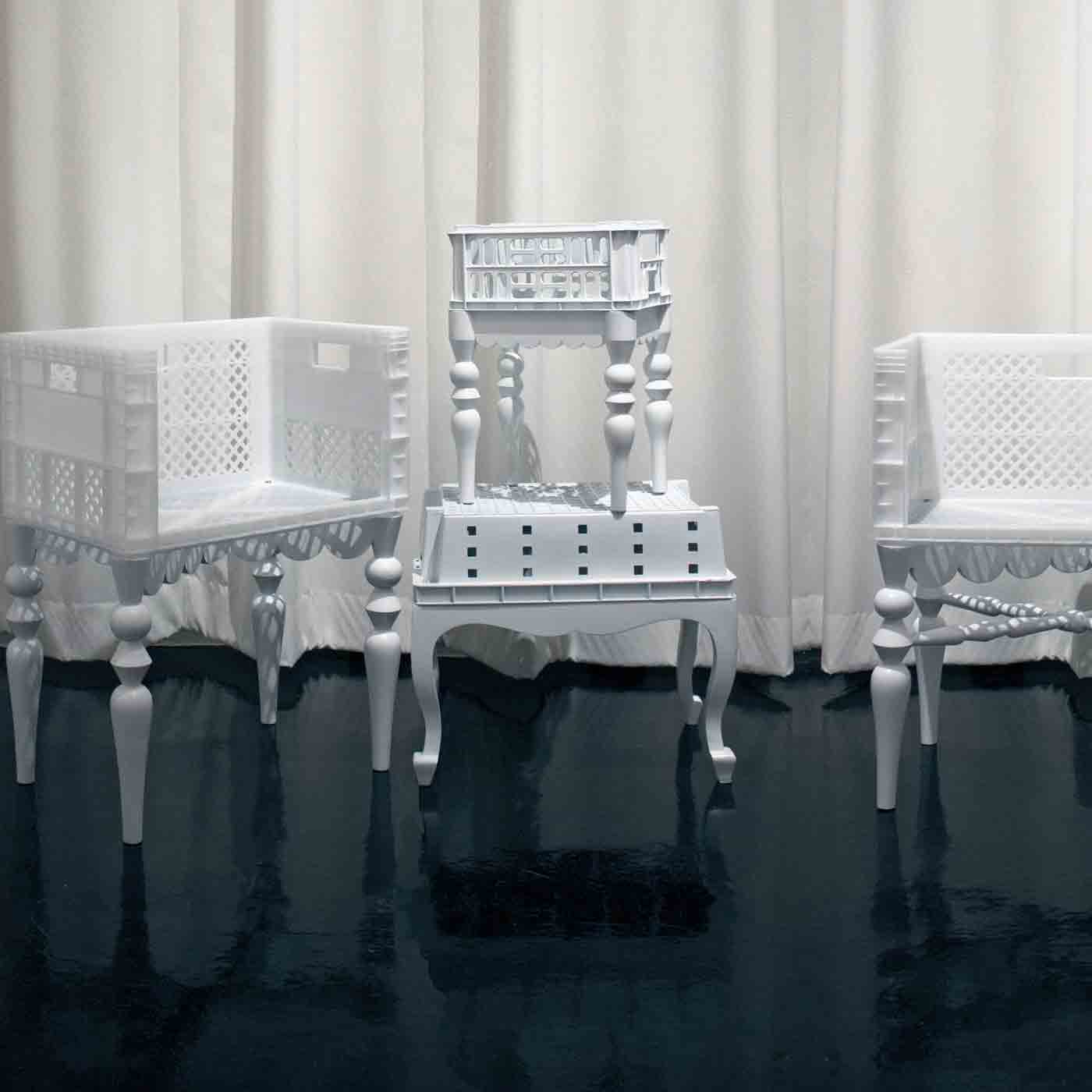

It is the aim of the exhibition Pure Gold to show this. It presents a total of 76 examples by 53 designers from the regions of Europe, Latin America, North Africa and the Near East, East Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia, and Southeast Asia, who have one clear thing in common. With varying degrees of perfection, all of these works are made either entirely by hand or with the help of just the simplest tools from used and worn materials – trash or the cheapest materials around. This means that expenditure on both equipment and operations is low. Works like those shown here can be made in the smallest workshops, within industrially more or less underdeveloped structures or independently at a private workbench.

To summarize: reuse here is much less “fundamental” and thus much less complex. The added value of the used materials is only partially due to the purely material qualities of the original material. It is also due to the use of the physical, compositional, configured

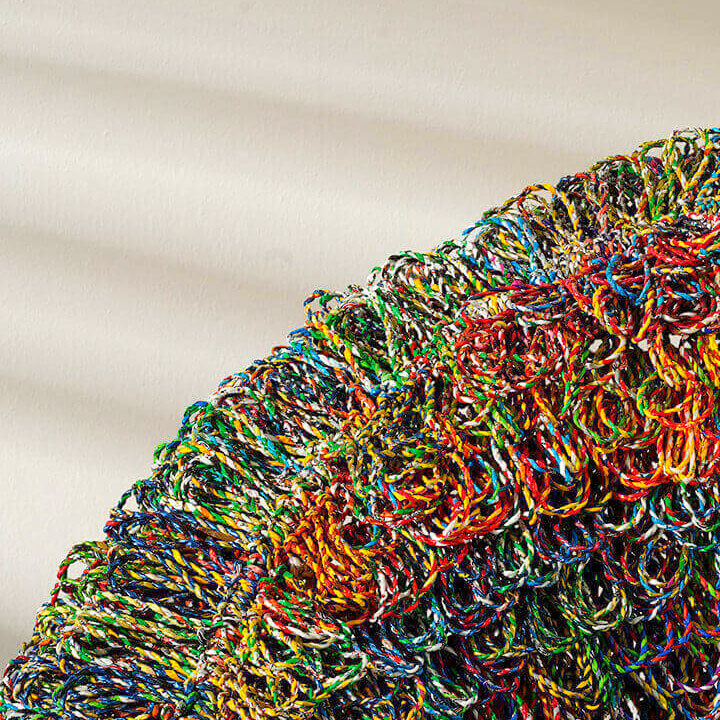

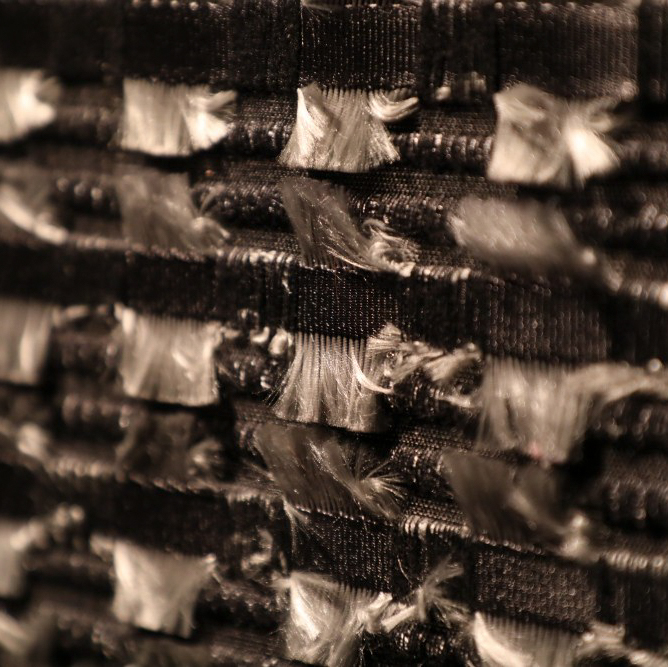

or just the aesthetic features of a deliberately selected or randomly found product. While industrial recycling aims to generate a quantity of products that are all as identical as possible (this is the only way to make a product like the Bayern football shirt), these “as found” strategies are primarily interested in using very specific known or hitherto neglected qualities such as formability, colour, firmness, haptics, or material structure and to add nuances in a new context. Sometimes this goes so far as to show the materials demonstratively while their original context and actual function can only be ascer-tained with a good deal of detective work. Probably no one would notice that Waltraud Münzhuber’s containers are nothing more than woven videotapes of various “favourite films.” And it would probably be just as difficult to see in Paul Cocksedge’s Styrene lamp a geometrically precise and yet relatively simple compilation of heat-reshaped polystyrene coffee cups. The origin of the Free Range stools by El Ultimo Grito is also not recognizable at first sight; these dented items are cleverly reshaped and compressed cardboard boxes.

Above all, it is the diversity of the found materials that makes this source of materials into a realistic alternative to the energy intensive reuse of standard raw materials. Found materials can be papers of all kinds, corrugated card, glass, car tyres, cork, denim, builders’ wood, plastic baskets, wooden planks, wool, fridge coatings, plastic bags, flip-flops, sticky and PVC tape, steel offcuts, cheap bags, and much more. If we add the characteristic at tributes to this list of materials – it is after all the physical and aesthetic features that speak for and against the use of a material – then we can get a rough idea of the immense imaginative scope that this nearly inexhaust ible stock of alleged trash holds for contemporary and future design.

Of course this form of design and production is not really new. It has similarities with the principle of the ready-made in the fine arts and with the adhocism propagated by Charles Jencks in the early 1970s [6], or with various aspects of the DIY movements from the 1960s to today, or the drop-out practices of the hippies in the 1960s and 1970s.

We can also recall here how articles of daily use are improvised in times of scarcity, originating from a completely different situation, but made and used with the same impulse and design principles as the works shown in this exhibition.[7]

In contrast to these “movements,” however (perhaps with the exception of objects of use made out of need and necessity), today’s development in design-motivated recycling (or recycling-motivated design) on show in this exhibition has no missionary urgency and comes with no abstract and idealistic ideology. Instead, these works derive from a mix of curiosity and imagination, an analytical perspective and often incredible patience, combined with crafts skills and a solid knowledge of the “raw materials” used. It is probably exactly this combination of very sober skill and artistic talent that has enabled this phenomenon in design to spread all around the world. This also means that these manually made and “improvised” works are no less significant than technologies developed for mass production and serial recycling.

For sure, in view of the 320,000 paper coffee cups discarded per hour (!) in Germany alone,[8] the importance of industrially managed recycling cannot be overemphasized. This is also true of the fact that manual production can simply and easily be carried out with the simplest of tools, and can lead to outstanding results, as this exhibition shows. The quality is not just in the design, but with the right handicrafts, also monetary.

The designer Stuart Haygarth holds an undisputed top place in this respect.[9] The Drop chandelier he designed in 2007 is made of hundreds of different carefully cleaned plastic bottle bases rearranged in a form resembling drops of water as the product’s key design idea. The production and material both show that this product could be made anywhere in the world, only if enough plastic bottles are available – but these are washed up on our shores everywhere.

The only reason why this classic example of exceptional upcycling cannot be included in this exhibition is its price of several thousand pounds sterling. This shows that we are not all that far away from the value of gold that the title of this exhibition suggests, particularly when we take a closer look at all the trash around us.

1 Bild, 5 November 2016, p. 1, p. 14.

2 See Neue Zürcher Zeitung, international edition, 22 February 2017, pp. 38/39.

3 See Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 23 March 2017, p. 19.

4 See Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, 19 March 2017, p. 24.

5 “Recycling“ is defined as “any process of use that processes waste products into products or materials to be used either for their original purpose or for other purposes.

This includes the use and processing of organic materials that are to be used as fuel or for back-filling” (§ 3 subsection 25, German Waste Management Act).

6 Charles Jencks, Nathan Silver, Adhocism, New York, 1973.

7 See Werkbund-Archiv, Blasse Dinge, Werkbund und Waren 1945 – 1949. Eine Ausstellung des Werkbund-Archivs im Martin-Gropius-Bau vom 12.8. – 8.10.1989, exhibition magazine,

Berlin, no year.

8 The number 320,000 is taken from Barbara Kuchler, “Über die Verhältnisse der anderen Leben,” in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 26 November 2016.

9 Stuart Haygarth, www.stuarthaygarth.com/

EXHIBITS FROM EUROPE

WORLD TOUR STATIONS

WORLD TOUR STATIONS